Written by Dr Robert A. Saunders and Dr Jack Holland

When you buy a beer, what does it say about you? Whether you order a pint of Guinness at the bar, grab a can of Carling on the go, drop a tenner on a Trappist ale in a swanky bistro or brew your own hopped-up IPA, all these little choices add to the international political economy of the ‘world’s favourite drink’. More so than wine or spirits, beer is about brand – and more importantly, visible branding. Tap handles and bottle/can art scream for recognition, while beer companies spend billions in advertisements and sponsorships to make sure their suds are front-of-mind when you order your next cold one. The global beer market was valued at US $520 billion in 2015 and estimated to exceed $750 billion by 2023.

Beer, which accounts for three-fourths of the global alcohol market, is so universal that some economists have even used its cost ratio to compare real wages across national economies. Taking the UK as a baseline, one needs to work one half-hour at minimum wage to earn enough for a cold one. In the Republic of Georgia, it takes a minimum-wage labourer 30 times that to accumulate enough cash for a pint; Israel, Brazil, and Romania are 1:1 in terms of minimum-wage hours to beer purchases. (Note: For those cerevisaphiles willing to relocate, Puerto Rico is currently the cheapest place in the world for beer-drinkers.) However, such comparisons are distorted by pro- and anti-beer taxation policies. In the Czech Republic, the highest per capita nation in terms of beer-drinking, it has long been an informal rule of politics that any government that raises the price of beer will fall in a year, whereas in the Nordic countries, taxes are so high that one can rent a bicycle for less than the price of a decent draught.

Nominal price of beer according to GoEuro

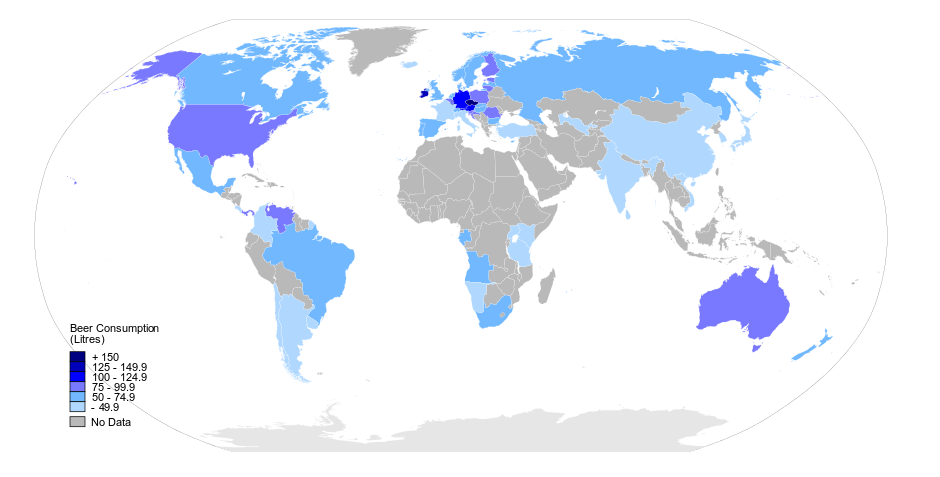

Beer is not for everyone though. For example, in the Muslim world, beer consumption is extremely low due to religious injunctions on drinking alcohol. Historically speaking, beer has also had an (arbitrary) association with masculinity, thus resulting in a measurable gender disparity in terms of consumption. Guinness, perhaps the leading pioneering in beer marketing, has long employed ways to work against and with the gender gap, from marketing its stout as the ‘healthy option’ for expectant mums to a nod-and-a-wink approach towards West Africans who took the company’s slogans ‘Guinness for Strength’ (1934) and ‘Guinness Gives You Power’ (1962) as references to sexual prowess. However, a recent academic global study finds that men and women now consume roughly the same amount of alcohol, including a marked rise in women’s consumption of beer largely due to corporations actively targeting women in terms of product development and advertising.

Worldwide beer consumption 2009

A drinking tour: beer as global history

Beer emerged on the world stage over 7,000 years ago, becoming – according to historians and anthropologists – one of the driving forces in civilizational development. The Sumerians, Egyptians, and Celts, among other ancient peoples, possessed deities associated with the intoxicating beverage. Beer shaped agriculture, fuelled armies and ignited conflicts, just as it lubricated the work of monks, philosophers and statesman (even playing a role in the writing of the US Constitution). So important was it to medieval health, the Bavarians decided to regulate beer production over 500 years ago, instituting the Reinheitsgebot or Purity Law, which stipulated (that is, limited) what could go into beer. Due to its ability to keep unspoiled, its high calorie content, and its guaranteed protections against many water-born contagions, the beverage became extremely popular in Victorian England, literally fuelling the workers of the Industrial Revolution.

Given the requirements of brewing, beer has a long history of localisation, and beers have tended to reflect the terroir of their production. However, as global trade expanded with European imperialism, so did the reach of certain beers as well as the geographic diversity of the sourced ingredients. Most famously, the British developed a process for cellaring beer in their ships’ hulls, leading to the creation one the most popular styles around: India Pale Ale (IPA). German migration after the failed Revolution of 1848 spread beer knowledge far and wide, bringing the Americas into the beer mainstream with new breweries in Canada, Mexico and the US; decades later, German overseas expansion would result in the first breweries in Sub-Saharan Africa, China and Japan. Prohibition in the US resulted in a temporary downturn in global beer production, which was quickly followed by massive expansion after World War II as a few large companies sought markets overseas in decolonising states in Asia and Africa (not insignificantly, Congo’s first president, Patrice Lumumba, began his career as a beer salesman).

Since the 1970s, a ‘craft beer revolution’ has been underway which has transformed the global market. Responding to the post-Prohibition of consolidation of beer production in a handful of giant firms, ‘bathtub brewers’ in the US began to develop tasty, complex and labour-intensive beers that reflect the locality in which they originated. Concurrently in the UK, the Campaign for Real Ales (CAMRA) attempted to reverse the trend towards homogenisation in brewing, urging British citizens to reject globalisation via the ubiquitous ‘lager’, and rediscover a submerged history of ale-brewing (and traditional pub drinking) that shaped modern England.

Paradoxically, neoliberalism and globalisation both abetted and challenged these trends, making it easier for transnational companies to buy up breweries around the world and export their products nearly everywhere. Belgian and Czech beers flooded the Anglophone world, encouraging taste palettes to evolve. This occurred just as global giants like InBev (a merger of Belgium-based Interbrew and Brazilian-based AmBev) acquired old stalwarts like Anheuser-Busch, ensuring that one can find their ‘usual’ from Uppsala to Ulaanbaatar (in 2014 the company commanded over 20 per cent of the world market in sales). However, we should not lose sight of the fact that this state of affairs leads to environmental degradation as increasingly-large carbon footprints are produced in order to supply this growing thirst for beer, from demands on water resources to the emissions produced in transportation to energy consumed through packaging, refrigeration, and recycling.

The craft beer revolution has been led by an alliance of beer-enthusiasts, who sought to distinguish their offerings from ‘Big Beer’, and found purchase with committed ‘locavores’ seeking to support their local brewer (though, increasingly, these ‘local’ offerings are travelling farther and farther from their points of origin). Across the global North, craft beer abounds: thousands of new breweries have opened in the US in the past decade with more on the horizon. The UK, Scandinavia, and the Netherlands have kept apace, prompting medieval brewing cultures in Germany and Belgium to respond to the new wave. Even in the wine- and spirit-drinking realms of southern and eastern Europe, the trend is mounting. The most immediate beneficiary of this new state of affairs is the hops industry. Humulus lupulus is the essential element of modern beer, and as result, getting the best hops has become somewhat of an obsession. Whether it’s Fuggle, Saaz or Citra, every brewer is on the hunt for the best, with the price passed through to you the consumer.

Baguio Craft Brewery, Philippines. Credit: Anton Diaz.

You are what you drink: beer as identity

Perhaps more so than any other beverage, beer choice reflects identity. Some people always drink ‘the usual’, typically a mass-produced and comparatively inexpensive pilsner (labelled a ‘lager’ in the UK). Taking its style name from the Bohemian city of Plzeň, the straw-coloured brew dominates the world via brands like Budweiser (US), Heineken (Netherlands), and Molson (Canada), as well as Tsingtao (China), Sapporo (Japan), and Brahma (Brazil). While these beers are certainly global in scope, they are also often specifically chosen by beer-drinkers in their countries of origin for their ‘national’ character. Other beers such as Foster’s, Red Stripe, and Corona have traded on their ability to export the essence of their providence to faraway shores, allowing the drinker to capture a bit of the ‘manliness’ of the Australian Outback, the ‘friendly vibes’ of Jamaica, or the ‘laid-back attitude’ of the Mexican Caribbean, respectively.

Beer adverts have drawn on national and gendered cultural scripts

However, these beers are now making room for an ever-growing host of craft upstarts. Ranging from hopped-up West Coast IPAs to sour ‘wild beers’, and from high-alcohol imperial porters to fruity low-alcohol lambics, there is no shortage of tantalising offerings in the world of beer, whether one is at a bar, a restaurant, a beer shop or the local grocery. And with this cacophony of brews comes the market problem of differentiation. In seeking to distinguish their products from those of rivals and carve out a consumer segment willing to pay higher prices, brewers have developed marketing strategies that engage popular culture in novel ways. Take for example the case of two geopolitically-inflected brews, namely the BrewDog’s ‘Hello, My Name is Vladimir’ from Scotland, and Norwegian brewery 7 Fjell’s ‘The Donald Ignorant IPA’.

In an otherwise satirical promotional piece on its website, BrewDog had this to say about its ‘Vladimir’ beer:

The sick, twisted legislation brought about in Russia that prevents people from living their true lives is something we didn’t want to just sit back and not have an opinion on. Our core beliefs are freedom of expression, freedom of speech and a dogged (no pun intended) passion for doing what we love. Thus, we are donating 50% of the profits from this beer to charitable organisations that support like minded individuals wishing to express themselves freely without prejudice.

While 7 Fjell’s ‘Donald’ ale included the following labelling:

US of A. The greatest country in the world. Potentially led by loose cannon who only looks out for himself… Inherited wealth and bankruptcy en masse in his wake. A narcissist who lives in a gold tower, wants to build a wall between the US and Mexico, deport 11 million people, undermine NATO in the harshest political climate since the USSR collapsed, try to shame Gold Star families, bullying his way pretty damn near the White House, and the list goes on. Generally speaking, The Donald is not a very nice guy.

Taking the piss: beer as resistance

In our journal article ‘The Ritual of Beer Consumption as Discursive Intervention: Effigy, Sensory Politics, and Resistance in Everyday IR’ we look at these two beers from the premise that popular culture is a political battlefield in international studies; that various contestations are always going on where parties are ‘fighting’, ‘winning’ and ‘losing’. On this view, beer can be thought of as both popular and material culture. It is popular culture insofar as it speaks to the political identity of drinkers, and material culture as it is endowed with affective properties such as taste and smell. These reveal the way consumers both express their identity and inhabit the consumption experience in a socially situated and culturally resonant manner; the practice of pub-going or other public forms of drinking being a good example. Perhaps most fundamentally, unlike other cultural products like films or novels, beer is actually imbibed, leading to inebriation and encouraging the production of a variety of emotions ranging from joy to rage. More than a market choice taken by rational consumers looking for the lowest possible price, beer drinking produces politics and, potentially, sites of political resistance too.

How should we think about the politics of beer consumption in this context? Obviously, consumers of these beers are expressing their desire to become altered through alcohol, but in the context of ‘taking the piss’ (which is etymologically related to an older instance of highly-gendered British slang, i.e. ‘piss proud’, referring to an empty or false male erection), they are also attempting to deflate the exaggerated ego of either Trump or Putin. While the brewers may think of this as part of the brand – a bit of fun that helps you to part with your money – we as students of global politics should not ignore the way that culture conveys, and even retools, a number of important geopolitical considerations, like public attitudes to world leaders. In this case, drinkers can actively perform their political resistance through buying and conspicuously consuming certain kinds of beer.

The public house as public space?

Beer Resources

Bostwick, W. (2014). The Brewer’s Tale: A History of the World According to Beer. New York and London: W.W. Norton.

Hennessey, J. and Smith, M. (2015). The Comic Book Story of Beer: The World’s Favorite Beverage from 7000 BC to Today’s Craft Brewing Revolution. Berkeley, CA: Ten Speed Press.

Hindy, S. (2014). The Craft Beer Revolution. New York: Macmillan.

van Wolputte, S. and Fumanti, M. (2010). Beer in Africa: Drinking Spaces, States and Selves. Münster: LIT Verlag Münster.

Kirkby, D. (2003). “Glorious Beer”: Gender Politics and Australian Popular Culture. Journal of Popular Culture, 37(2), pp. 244–56.

MacGregor, R. M. (2003). I Am Canadian: National Identity in Beer Commercials. Journal of Popular Culture 37(2), pp. 276–86.

Nichols, E. (2016). “What on earth is she drinking?” Doing Femininity through Drink Choice on the Girls’ Night Out. Journal of International Women’s Studies, 17(2), pp. 77–91.

Pritchard, I. (2012). “Beer and Britannia”: Public-House Culture and the Construction of Nineteenth-Century British-Welsh Industrial Identity. Nations and Nationalism, 18(2), pp. 326-345.

Saunders, R. A. and Holland, J. (2017). The Ritual of Beer Consumption as Discursive Intervention: Effigy, Sensory Politics, and Resistance in Everyday IR. Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 46(2), pp. 1–23.

Wagman, I. (2002). Wheat, Barley, Hops, Citizenship: Molson’s “I Am [Canadian]” Campaign and the Defense of Canadian National Identity through Advertising. Velvet Light Trap, 50, pp. 77–99.