Written by Dr Chris Clarke

When we think about borrowing today, we tend to assume it takes place in the context of money. This is perhaps not surprising, given that seemingly more and more of everyday life is paid for using borrowed money. For instance, mortgage and consumer debt is commonly used to pay for such things as housing, cars, university tuition fees and basic food needs.

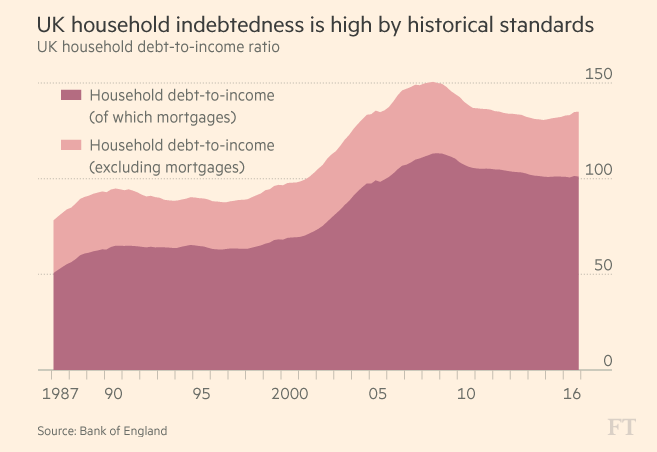

In recent decades, mass indebtedness has come to define some national political-economic conditions, even in the rich global north. Without high levels of access to borrowing, benchmarks for the health of major world economies would look very different. A dependence on consumer spending is on the rise even in emerging economies like China, as well being one of the hallmarks of an ‘advanced’ national economy such as the UK. High levels of borrowing are required to sustain increases in levels of spending, especially in the context of stagnating real wages and living standards.

‘We must live within our means’

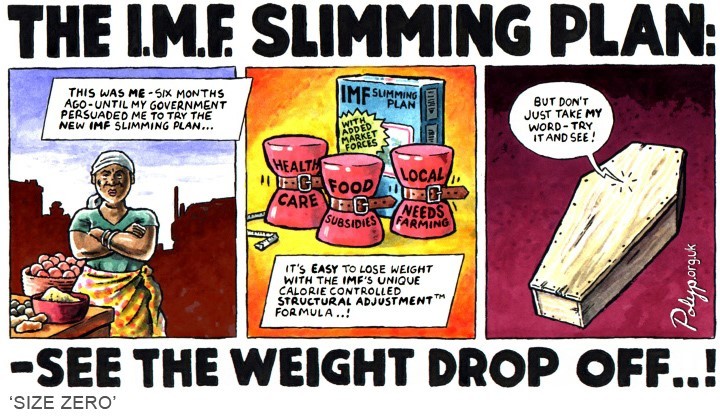

A cruel irony is that while ordinary people are implicitly asked to rely on private debt rather than wages, they are also explicitly told that collectively as a nation ‘we must live within our means’ due to the unsustainability of public debt. What is usually meant by this is that governments should ‘balance the books’ and attempt to borrow less money through the pursuit of austerity measures and state restructuring. Whether in rich countries after the Global Financial Crisis or in poor countries after successive debt ‘crises’ in the 1980s and 1990s, the burden of such state policy is disproportionately felt by women, as well as racialised and marginalised people, because they are the ones most likely to rely on the sorts of services being retrenched.

A critique of the structural adjustment programmes of the International Monetary Fund

The household budget analogy

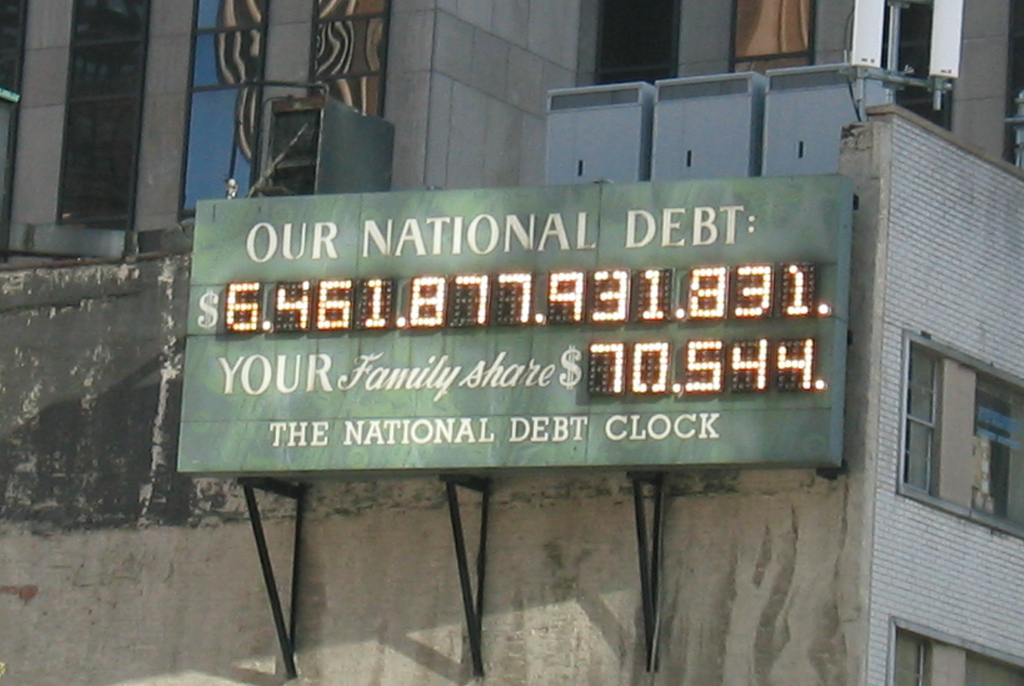

A second tragic irony is that politicians continually make the claim that a national government budget is analogous to a household budget. Just like individual households, the reasoning goes, governments should pay their debts and only borrow and spend what they can afford. As UK Chancellor of the Exchequer George Osborne once said: “We are asking the British people to reduce the record budget deficit and pay off the national credit card”. However, there are at least three reasons why this claim is nonsensical.

The National Debt Clock in New York was devised by a real estate developer Seymour Durst and reinforces the household budget analogy by making up a ‘family share’ of US debt

First, those from whom a government borrows money cannot simply ‘break up’ that sovereign government in order to sell their assets and recover losses in the case of default. In other words, aside from conditions of militarised war and regime change, sovereign governments cannot just cease to exist. For states this means, with the important exception of when developing country debt repayments are aggressively pursued by international creditors, they will almost always enjoy a degree of power in debt negotiations that would not exist at the household level. Other types of creditors, by contrast, can deploy debt discipline on households through such means as bankruptcy procedures and aggressive debt collection. Within the household, there is not the same backstop and so ordinary people, especially women, face depletion and the brunt of the costs of social reproduction.

Second, the act of borrowing looks very different when the entity borrowing money also has the ability to print money. Sovereign states (and some groups of states) control the money supply, which is an advantage that households obviously do not enjoy. States can ‘create’ money through their central banks to buy bonds from their finance ministries, who in turn can use the money and interest from bond sales to finance government borrowing. Under very few circumstances could an ordinary borrower create the money with which to service or repay a debt obligation.

Third, levels of government borrowing and spending have an effect on broader political-economic conditions in ways that one household’s borrowing and spending clearly does not. Often it might be sensible for a government to borrow to pay for investments that have broader desirable outcomes, such as in basic infrastructures, which is one of the basic tenets of Keynesianism. In the aggregate, of course, household debt does have enormous impact on political-economic conditions, but no single household enjoys the power bestowed by a government’s unique position when it comes to the specific act of borrowing.

IPE scholar Mark Blyth on the fallacy of pursuing austerity after the Global Financial Crisis

Good borrower, bad borrower

The household budget analogy is in a sense a morality play, in which ordinary people are asked to acquiesce to the necessity of austerity and state restructuring because of the moral ‘bad’ attached to debt. Such morality plays operate in ways to convince people that financial failures are their own, a deeply personal condition whether on the individual, household or national level.

“If you have maxed out your credit card, if you put off dealing with the problem, the problem gets worse” David Cameron

The creation and maintenance of such cultural and affective dispositions towards borrowing is a deeply political and contradictory matter. On one level, it can operate through particular cultural tropes. For instance, just like a Lannister in Game of Thrones, there is the simple idea that one should always repay one’s debts.

On another level, there is also a complex delineation between good and bad borrowing based on ability to service debt. For instance, if someone is indebted with an amount of borrowing around £300,000 on a mortgage loan, they might be deemed by government and broader social mores as behaving perfectly prudently. After all, the debt allows them access to the benefits of homeowner society and various governments around the world subsidise and promote mortgage borrowing in general. On these terms, they are making a sound debt-based investment grounded in the expectation of house price inflation. As long as they continue to service the huge debt, they are praiseworthy.

By contrast, if someone were indebted by a much smaller amount of say £300 or £3000 to a payday lender or credit card company, they would not necessarily be judged to have behaved as prudently. Presumably the interest rates they face and the credit scores they acquire would be much worse than the mortgage borrower, even though bizarrely they have borrowed much less money. In this instance, the borrower of the smaller amount could find it more difficult to service the debt given the higher costs of their shorter-term borrowing. They are more likely to be at risk of default and thus they are unpraiseworthy.

This is a stylised example, but the point is that not all forms of borrowing are equal. What matters is the ability to service debt (and not necessarily repay). Indeed, some people borrow money continually to meet outstanding loan repayment obligations and this suits lenders and governments dependent on debt-fuelled consumer spending just fine (until crisis hits). For instance, in 2017 consumers in the US had over $1.02 trillion in outstanding revolving credit, a record high.

A trailer for the morally-charged UK TV programme on debt collection ‘Can’t Pay? We’ll Take it Away’

So, ‘neither a borrower nor a lender be’?

We could be forgiven for thinking that one way out of some of the worst conditions of heavy indebtedness would be to remove ourselves from the chains of borrowing money altogether. One recent development that builds on this line of thinking is the so-called ‘share economy’, which is a set of online platform and mobile based firms that seek to ‘democratise’ and ‘disrupt’ a number of areas of political-economic activity. The most well-known firms operate in the area of ride sharing and accommodation, with the stated aim of allowing users to ‘share’ services and assets to the ostensible benefit of all parties concerned.

A visual representation of the companies involved in the sharing economy, with “empowered people” at the centre - Image courtesy of Jeremiah Owyang

However, the whole concept of the ‘share economy’ as it has come to mass scale appears to be flawed. As opposed to anything close to an economy providing for the ‘sharing’ and ‘borrowing’ of existing resources, platform firms tend to be reproducing patterns of power and inequality – such as new monopolies, conditions of precarity, and the spread of ‘zero-hours’ contracts – based on a system of extracting rent from owned assets. Much the same applies for those firms that provide small loans through online platforms, such as peer-to-peer lenders. While they emphasise the social aspects of borrowing and lending money, they increasingly tend to operate much like major banking institutions.

More productively, recent innovations in digital and mobile technologies are being harnessed by those interested in platform cooperativism. Examples of successful platform cooperatives include Peerby, a neighbour-to-neighbour goods sharing platform, and Loomio, a co-operative that builds open-source software for collaborative decision making. While such platforms might not remove the need for borrowing money in society altogether, at the very least they remind us how, as Karl Polanyi would also surely stress, the act of borrowing is not necessarily a market-based monetised endeavour.

Borrowing Resources

Blyth, M. (2013) Austerity: The History of a Dangerous Idea. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Clarke, C. (2016) Ethics and Economic Governance: Using Adam Smith to Understand the Global Financial Crisis. Oxford: Routledge

Joseph, M. (2014) Debt to Society: Accounting for Life under Capitalism. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press

Soederberg, S. (2014) Debtfare States and the Poverty Industry: Money, Discipline and the Surplus Population. Oxford: Routledge

Brassett, J. and Rethal, L. (2015). Sexy money: the hetero-normative politics of global finance. Review of International Studies, 41(3), pp. 429-449.

Dow, S. C. (2015). The Role of Belief in the Case for Austerity Policies. The Economic and Labour Relations Review, 26 (1), pp. 29-42.

Rogers, C. and Clarke, C. (2016). Mainstreaming Social Finance: The Regulation of the Peer-to-Peer Lending Marketplace in the UK’, British Journal of Politics and International Relations, 18: 4, pp. 930-945.

Stanley, L. (2014) ‘We’re Reaping What We Sowed’: Everyday Crisis Narratives and Acquiescence to the Age of Austerity. New Political Economy, 19 (6), pp. 895-917.