Written by Dr Zoë Pflaeger Young

The coffee paradox

Coffee is one of the world’s most valuable exported commodities with an estimated 1.6 billion cups of coffee consumed in the world every day. From its origins in the mountainsides of Ethiopia, coffee has come to play a significant role in Western society, stimulating intellectual thought in Continental coffeehouses, sustaining workers in the factory system during the Industrial Revolutions of Europe and North America, and bestowing cultural capital in the revived coffeehouse scene of the 1920s and 1930s. More recently, coffee has undergone what Stefano Ponte dubbed a ‘latte revolution’. Coffee bars and café chains, in which consumers can choose from an extensive range of speciality and gourmet coffees, have spread dramatically and are increasingly becoming global, expanding to traditionally tea-drinking countries in parts of Asia, such as India, China and Japan. However, the politics of coffee are complex and the history of the coffee industry also has a dark side.

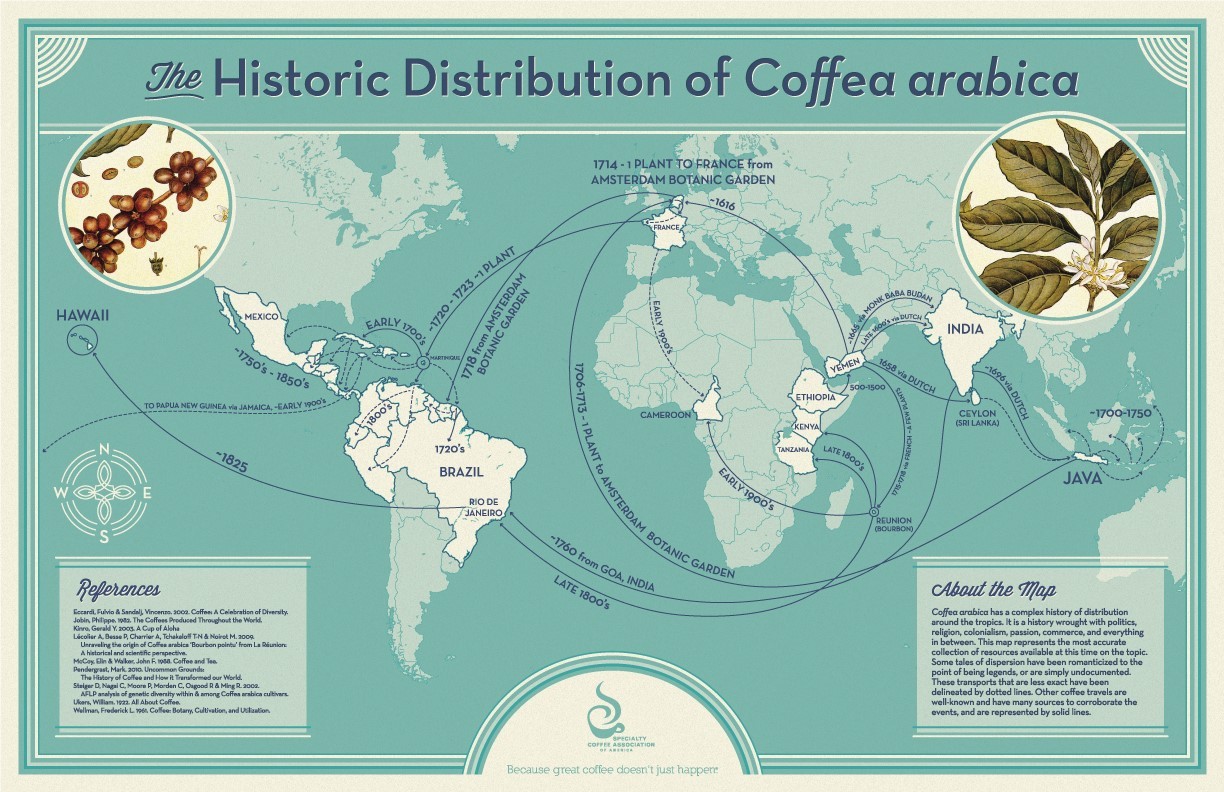

Initially a jealously guarded secret of the Turkish Empire, coffee production assumed a significant role in European colonialism. The Dutch began cultivating coffee in the seventeenth century in their colonies of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka) and later Java, Bali and other islands of the East Indies, enslaving local populations as coerced labour to grow and harvest the coffee. The French first grew coffee in San Domingo (now Haiti), primarily through the forced labour of imported African slaves, becoming the world’s leading coffee exporter in the eighteenth century. Growing demand for coffee across Europe intensified coffee production in British and French colonies in the Caribbean, Central America and later Africa, and boosted the Atlantic slave trade. This highly unequal and complicated history of coffee is important in understanding the modern coffee industry, as these practices associated with the expansion of coffee production continue to shape the social, economic and ecological development of these societies. For some, there is concern that modern coffee production echoes these colonial relations, with farmers in the Global South producing coffee for consumers in the Global North having never actually tasted their own coffee.

Coffea arabica is indigenous to Ethiopia and now makes up 70% of global coffee production. Source: Speciality Coffee Association of America

However, coffee production has played an important role in development, with coffee exports linked to development ‘success stories’ in certain countries at particular times, such as Brazil in the nineteenth century, Colombia and Costa Rica in the 1920s, and Kenya and Cote d’Ivoire in the 1960s and early 1970s. In some cases, this success has led to further growth and diversification. Coffee is produced in more than 50 countries in the Global South and around 125 million people worldwide depend on coffee for their livelihoods. While coffee is mainly produced in plantations in countries such as Brazil, the leading coffee producer, the majority of the world’s coffee in produced by smallholder farmers, who dominate coffee production in countries such as Colombia, Mexico and Costa Rica as well as in almost all African countries. Coffee farming in Africa is dominated by smallholdings varying between half a hectare and 10 hectares in size. Although their global market share may be modest, coffee has been a significant export earner for many of the 25 coffee producing countries in Africa as well as an important source of income for smallholder farmers.

The paradox at the heart of the modern coffee industry: a ‘coffee boom’ in consuming countries and a ‘coffee crisis’ in producing countries (Daviron and Ponte)

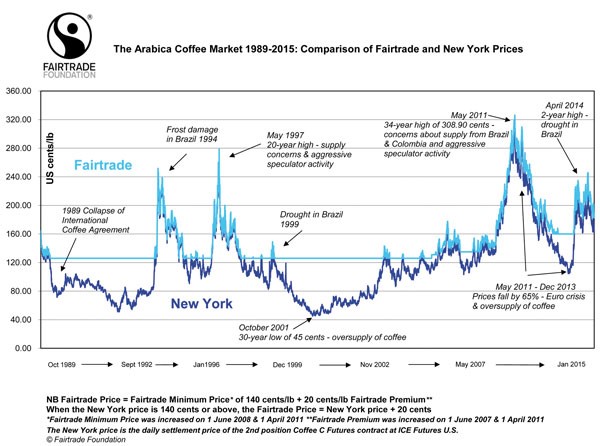

Global coffee consumption has remained relatively high and stable and coffee roasters have enjoyed increasing profits, but coffee producers have struggled to make a living with incomes falling below the costs of production, such as during the crisis of 2001-2005. This paradox can be explained by structural changes in the organisation and governance of the global coffee industry following the functional collapse of the International Coffee Agreement (ICA) in 1989.

The coffee crisis

Coffee was one of first global commodities to be regulated and this was relatively successful. Under the ICA regime (1962-1989), producing and consuming countries collaborated reasonably successfully to raise and stabilise coffee prices through a quota allocation system. The regime did experience some political problems, but was not clearly driven by any particular actor, with power shared between producing and consuming countries. Roasters in consuming countries were increasing their leading role through branding and advertising, but their control was limited by the quota system and by government control in producing countries over marketing and quality control systems. Government coffee boards responsible for exporting coffee, although imperfect, provided coffee producers with some protection and a collective voice, and retained control over coffee stocks.

Following the collapse of the ICA, coffee producers have experienced historically low coffee prices in 2001-2005 and again in 2013 as well as significantly higher levels of price volatility, linked not only to the end of the price stabilisation mechanisms, but also to increased speculative activity. Due to the disbandment of government coffee boards under domestic processes of liberalisation, many coffee producers have been exposed to the full volatility of this market. As demonstrated in the documentary Black Gold, the modern coffee industry has become highly unequal with a concentration of power among coffee roasters and international traders, increasingly able to dominate the market and capture the value of coffee, and a fragmentation of coffee producers with little voice or collective bargaining power. This can help to explain the paradox and has also given rise to attempts to enable coffee producers to capture more of the value of their coffee as well as to ensure they receive a stable and sustainable livelihood.

Fair trade coffee

Coffee has been a flagship Fair Trade commodity: it was the first product to be Fairtrade-certified and remains one of the largest, although other products such as bananas and cocoa have also become popular. Despite the long-term impact of the economic recession, Fairtrade coffee sales have continued to grow in the UK, the largest Fairtrade market, accounting for about 25 per cent of the roast and ground market. Fair Trade began as an alternative trade movement aimed at establishing trading links between marginalised producers in the Global South and progressive, politically-motivated consumers in the Global North on the basis of the principles of social justice, equity and sustainability.

These principles have continued to shape the Fair Trade movement as it has moved into the mainstream market through the introduction of Fairtrade certification. Formalised as the Fairtrade mark, certified products must meet internationally-agreed Fairtrade standards designed to ensure that producers receive a guaranteed minimum Fairtrade price that covers the cost of sustainable production as well as an additional social premium to be invested communally by producer organisations. The standards also include objectives to facilitate long-term trading partnerships and enable greater producer control over the trading process.

In the case of coffee, registered producers must be smallholders organised into democratic and political independent producer organisations or cooperatives. National labelling organisations, such as the Fairtrade Foundation in the UK, work to certify, monitor and promote Fairtrade products as well as to raise awareness and educate consumers. Their work is coordinated under the umbrella of the international organisation, Fairtrade International. Despite the stated aims of equitable trade and producer empowerment, concerns have been raised that these principles are at odds with the motivations and actions of the powerful retailers and corporations that have become included in fair trade through certification.

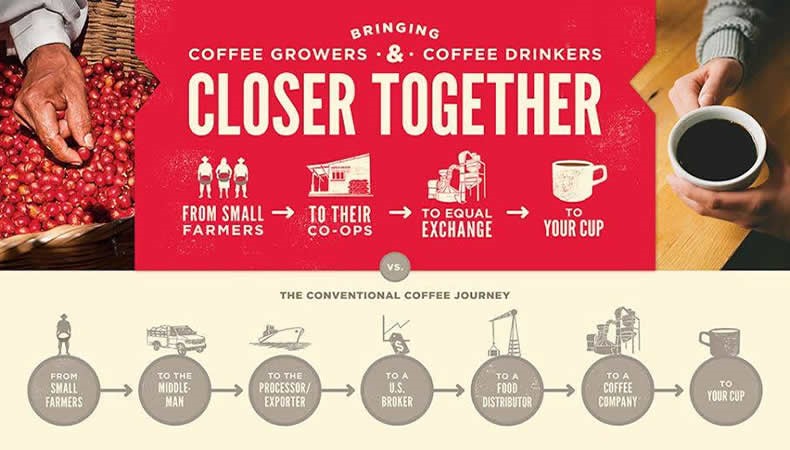

While these are valid concerns, it is also important to recognise the efforts of alternative trade organisations (ATOs) that have continued to work with producer organisations to ‘go beyond’ the minimum Fairtrade standards. Organisations, such as Cafédirect and Equal Exchange, not only commit to selling 100 per cent Fairtrade certified products, but they also typically work more directly with producer organisations to reinvest profits and improve quality as well as aiming to ensure greater producer representation in the ownership and management of these organisations.

Equal Exchange illustrate how their supply-chain supports small farmers

ATO initiatives can work with producer organisations to improve producer knowledge of the coffee industry and to strengthen their collective bargaining power so that producers can retain greater control and capture more of the value of their product. One example is the Ethiopian Coffee Trademarking and Licencing Initiative through which Ethiopian coffee producers were able to trademark three of their fine coffee brands and licence their distribution with the aim of de-linking their coffee price from the volatility of the commodity market and instead capturing a higher and more stable proportion of the retail value. Single-origin coffee sold in the speciality market is a small but significant strategy of differentiation and de-commodification that seeks to reverse the trend towards homogenisation and concentration of power that dominates the global coffee industry.

Coffee and gender

The role of women in the global coffee industry is an important but often neglected area of analysis. It is often assumed that coffee is a ‘male crop’, but, particularly in the African context, it is actually women who contribute a significant portion of the labour in coffee production. The coffee crisis has exacerbated the multiple burdens placed on women, as women struggle to combine their productive and reproductive roles, engaging in a variety of income-earning strategies to supplement declining coffee incomes and to sustain the household. While women carry out much of the productive work associated with growing and harvesting the coffee, it is men that own the land and retain control over income derived from coffee production as well as dominating decision-making processes at the household and cooperative level.

In the case of a Fairtrade-certified cooperative in Kenya, women account for one third of the cooperative membership but there have been no female members on the elected management committee. Fair Trade has a stated aim to address gender inequalities and to support women’s empowerment, but feminists have argued that more needs to be done to actively address existing gender norms that may present a barrier to women’s participation in Fairtrade and their ability to share in the gains. For example, it is important to involve men in discussions about how women could be supported in their reproductive work so that they are able to attend training sessions and can play a more active role in cooperative decision-making processes. One innovative practice in raising awareness about gender issues in coffee has been the emergence of the concept of ‘Women’s Coffee’, in which female producers have direct access to the income from their coffee and gain greater experience in the marketing of their product. Such interventions remind us why recognising the unequal gender relations of trade remains a crucial task for IPE scholarship.

Coffee Resources

Daviron, B. and Ponte, S. (2005). The Coffee Paradox: Global Markets, Commodity Trade and the Elusive Promise of Development. London and New York: Zed Books.

Jaffee, D. (2007). Brewing Justice: Fair Trade Coffee, Sustainability, and Survival. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press.

Luttinger, N. and Dicum, G. (2006). The Coffee Book: Anatomy of an Industry from Crop to the Last Drop. New York: New Press.

Arslan, A. and Reicher, C. P. (2011). ‘The Effects of the Coffee Trademarking Initiative and Starbucks Publicity on Export Prices of Ethiopian Coffee’. Journal of African Economies, 5(1), pp. 704-736.

Pflaeger, Z. (2013). ‘Decaf Empowerment? Post-Washington Consensus Development Policy, Fair Trade and Kenya’s Coffee Industry’. Journal of International Relations and Development, 16(3), pp. 331-357.

Ponte, S. (2002). ‘The ‘Latte Revolution’? Regulation, Markets and Consumption in the Global Coffee Chain’. World Development, 30(7), pp. 1099-1122.

Watson, M. (2006). ‘Towards a Polanyian Perspective on Fair Trade: Market-Bound Economic Agents and the Act of Ethical Consumption’. Global Society, 20(4), pp. 435-451.