Written by Charlotte Godziewski

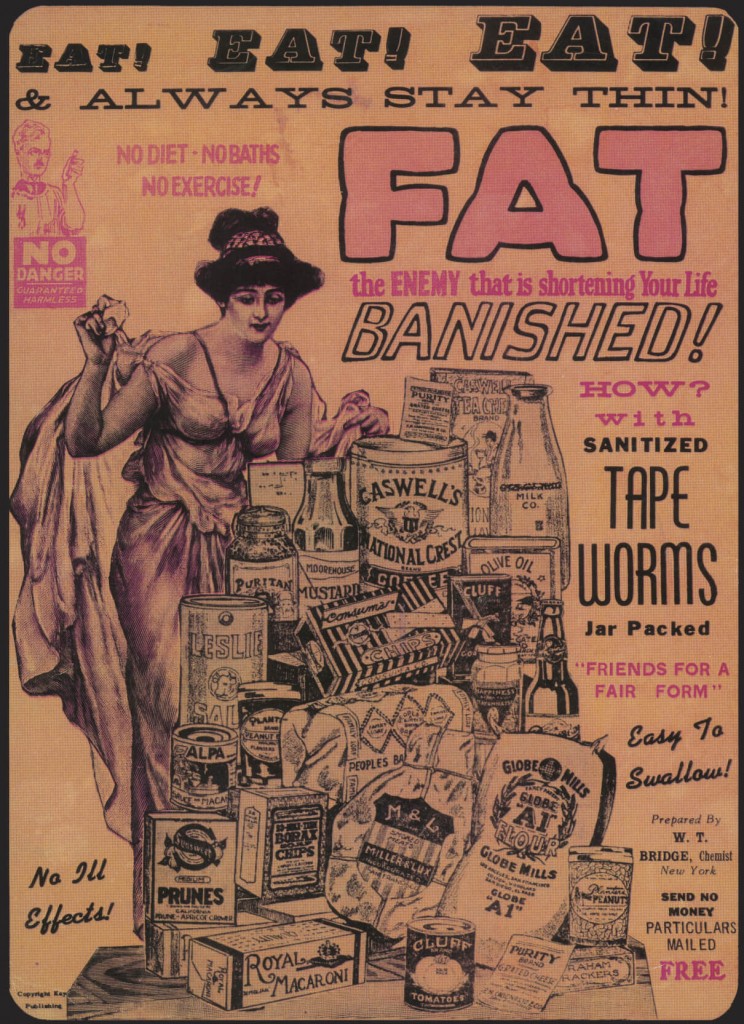

How do we diet? The vintage advert below says we can eat as much as we like so long as we take some ‘sanitized’ tapeworms (!). While this might seem an outdated and dangerous way to lose weight, it speaks to a long tradition of extreme diets and weight loss supplements that can range from mostly useless to sometimes lethal. Despite the allure of advertising, rapid weight loss usually comes with a decline in muscle mass, which in turn reduces the body’s basal metabolic rate and leads to rapid weight re-gain in the form of fat. Yet at a time when many people are becoming heavier, thinness is increasingly taken as a proxy for good health. Popular culture has a tendency to equate being thin with all kinds of positive attributes: self-control, success, ambition, liveliness. In turn, losing weight has become a moral imperative. Fuelled by such deeply ingrained beliefs, a multibillion dollar diet industry thrives on sustaining the idea that weight loss is necessary to achieve happiness. The flipside of this quest for thinness is the stigmatisation of and discrimination against overweight and obese people.

Governing diet

Recent years have seen body weight mobilised as a primary object of health governance. Obesity is linked to an increased risk of numerous non-communicable diseases; indeed the World Health Organization (WHO) estimates the number of deaths associated with obesity at 2.8 million per year. A number of studies that quantify the economic cost of obesity on national health systems have alarmed governments and pushed them to act. In the UK, the National Health Service has promoted Change 4Life, a project aimed to help citizens make educated healthy choices about their diets and physical activity. It aims to make people ‘food smart’, teaching them to read labels and ‘nudging’ them towards healthy choices. Individuals are thus expected to become responsible for their health, understood as weight, via ‘better’ consumption choices.

Change4Life: Be Food Smart TV advert

On this view, weight management is framed as a moral issue of individual responsibility, where the public costs – to the NHS and taxpayers – are set against the individual irresponsibility of eating unhealthy food. Whether intentional or not, such a moral economy can easily overlap with a wider social stigma against obese or sedentary people in general. Indeed, by focusing solely on the individual, public health initiatives neglect or even obscure the structural context of food consumption, which produces a food environment rich in high calorie, high sugar, yet cheap foods.

Why are public health policies stuck in the ‘individual responsibility’ narrative? Many public health initiatives rely upon the voluntary participation of private and public stakeholders’ like companies, campaign groups, and local government. Going back to the Change 4Life example, multinational corporate partners of this public health campaign include Danone, Britvic (a soft drink corporation) and major retailers such as Aldi and Asda. There is a strongly ingrained conviction that the food industry is an important “part of the solution” to the obesity problem. This ‘soft law’ approach to the governance of obesity has resulted in industry commitments such as food reformulation, better food labelling, code of conducts for advertising, and a focus on physical activity promotion. Note that these actions assume, ultimately, that food choice is a matter of individual responsibility and that the industry’s role is to enable consumers to become ‘food smart’. In addition to reinforcing the individual responsibilisation narrative, this allows food and drink corporation to absolve themselves from any form of responsibility for obesity, while even promoting themselves as responsible norm-setters. Some corporations are arguably complicit in perpetuating the victim-blaming rhetoric, for example by implicitly devaluing overweight/obese people.

Inequality and globalisation

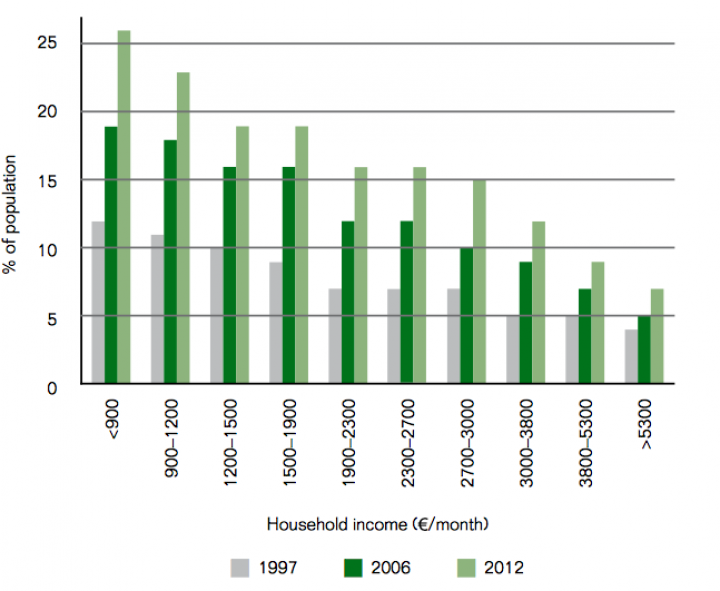

Reducing obesity to a moral issue of individual choice masks its complexity and its far-reaching, structural determinants. Socioeconomic inequalities deeply rooted in neoliberal capitalism play a major role in the distribution of poor diet and obesity. In the EU, people from low socioeconomic groups have double the risk of being obese compared to other population groups, and half of obesity cases in women can be accounted for by inequalities in educational status. Gender and racial inequalities also strongly impact on obesity prevalence.

Adult obesity prevalence in France by household income, 1997–2012

Again, overweight people face significant forms of discrimination and are often socially marginalised, which reinforces the structural effect of such inequalities. Indeed, the WHO report on inequalities and obesity draws attention to the potentially harmful and inequality-exacerbating impact of some public health policies. As such, it offers a number of possible interventions to consider, arguing that policies which focus on education miss the point that economically disadvantaged people may well know what healthy is, but it may not be either available or affordable.

There is evidence that free trade and foreign direct investment are linked to obesity as a result of the increased availability of cheap unhealthy foodstuffs and the weakened government capacity to implement public health regulations. Low and middle income countries (LMICs) have seen a rise in obesity as a result of globalisation – a phenomenon referred to as the global “nutrition transition”. Trade liberalisation, the growth of transnational food corporations and global food advertising have been linked to deteriorations of the quality of diets in LMICs, where obesity now exists alongside under-nutrition and nutrient deficiencies.

The partnership between the major Brazilian food corporation Sadia and British celebrity chef Jamie Oliver illustrates the Western-centric nature of the globalising food system. Together, their project Saber Alimenta is targeted at ‘educating’ young Brazilian school children about cooking. Jamie Olivier introduces the project thus:

“In the UK, I’ve worked hard to change people’s relationship to food for the better, and now, I want to try and bring that positive change to the rest of the world too”

This project has been vehemently criticised by a large number of Brazilian civil society organisations. They have accused it of undermining their long term efforts to preserve the indigenous, varied and healthy Brazilian diet, for being atrociously context-insensitive, and for effectively representing a distasteful marketing operation targeted at a vulnerable population group, i.e. young children.

Fat acceptance movements and body positivity

People who are overweight or obese are subjected to deeply ingrained prejudices and anti-fat biases, not least in the labour market, where they face difficulties finding a job and end up earning less on average than thinner colleagues. Obese people also face discrimination in the education system, in the health system by health professionals and in their everyday social life, where the predominant attitudes vis-à-vis excessive body weight often remain ruthlessly limited to ‘victim’-blaming and body shaming. The discrimination can be internalised by the victims, who are at high risk of suffering from depression, anxiety and low self-esteem.

Protest movements against this form oppression have been gaining momentum, which may be indicative of progressively changing mentalities. While ‘radical fat activism’ and ‘fat acceptance movements’ have been celebrated as a socially empowering movement, this type of movement attracts particularly large and vitriolic crowds of detractors who see body liberation as minimising or denying the harmful health consequences of obesity. By challenging anti-fat biases these political movements aim precisely to expose fat-phobia’s entrenchment in oppressive structures such as capitalism and patriarchy. They embrace a more holistic vision of ‘health’, highlighting the deleterious social and mental health consequences of fat-shaming and advocate to put an end to ‘victim’-blaming social attitudes towards obese people. However, some have criticised how the increased success of these radical movements is now accompanied by a corporate commodification of body positivity.

Dieting Resources

Boswell, J. (2016) The Real War on Obesity: Contesting Knowledge and Meaning in a Public Health Crisis. Palgrave Macmillan UK.

Guthman, J. (2011) Weighing in – Obesity, Food Justice and the Limits of Capitalism. University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles.

Hawkes, C., Chopra, M., & Friel, S. (2009) ‘Globalization, Trade and the Nutrition Transition’ in Labonte, R., Schrecker, T., Packer, C. and Runnels, V. (eds.) Globalization and Health: Pathways, Evidence and Policy. London: Routledge, pp. 235–262.

Rothblum, E. and Solovay, S. (2009) The Fat Studies Reader. New York: New York University Press.

Evans, B., Colls, R., & Hörschelmann, K. (2011) ‘“Change4Life for your kids”: embodied collectives and public health pedagogy’, Sport, Education & Society, 16(3), 323–341.

Garde, A., Jeffery, B., & Rigby, N. (2017) ‘Implementing the WHO Recommendations whilst Avoiding Real, Perceived or Potential Conflicts of Interest’, European Journal of Risk Regulation, 8(2), 237–250.

Glaze, S., & Richardson, B. (2017) ‘Poor choice? Smith, Hayek and the moral economy of food consumption’, Economy and Society, 46(1), 128–151.

LeBesco, K. (2011) ‘Neoliberalism, public health, and the moral perils of fatness’, Critical Public Health, 21(2), 153–164.

Labonte, Ronald (2017) ‘The hidden connection between obesity, heart disease and trade’, The Conversation

Richardson, B., & Gelhaus, L. (2015) ‘Shame on You: Fat Discrimination and the Food Industry’ Lacuna Magazine

Van der Zee, Renate (2017) ‘Demoted or dismissed because of your weight? The reality of the size ceiling’, The Guardian

Kelli Jean Drinkwater (2016) The Fear of Fat – The Real Elephant in the Room. TEDxSydney

Marion Nestle (2016) Big Soda. Big Obesity. #10 Podcast on “Reinventing Supermarkets” Podcast Series