Written by Dr Oscar Berglund

For those who have one, the mortgage is generally the largest debt we will ever have. It is a ticket to homeownership. It is what so many young people dream of but can now only get if their parents are able to lend a helping hand. The mortgage may not feel like a debt, because it enables you to buy a home (an asset) and it makes you feel richer, rather than poorer. But it is a debt, which means it plays a much larger role in the global economy than allowing people to buy homes. Financial products based on mortgages directly caused the global financial crash in 2007-8. They also left millions of households homeless and in debt.

The story of the sub-prime mortgage crisis, which grew into a much larger crisis in the global political economy is often told from the top down. Financial institutions wanted more mortgages. So mortgage brokers were incentivised to sell more mortgages. The people that they needed to sell to were in unstable and low-paid work, meaning that there was a greater risk that they would become unable to pay their monthly instalments. Moreover, this form of targeted mortgage lending is often racist, sexist and classist whereby ethnic minorities, women and people with the most unstable income get the worst interest rates. This makes their mortgages the most expensive and therefore the most lucrative for the bank. However, the risk that this lending posed led to the sub-prime mortgage crisis, a story which is told in the film The Big Short in greater detail and with better acting than I could do here. What The Big Short does not explain is how this crash affected the households that could not pay their mortgage and defaulted.

Scene from the movie 'The Big Short' - The securitisation of subprime mortgages

From the top down perspective, the story of the sub-prime crisis appears as a straight question of how to restructure regulations so as to save and stabilise the financial system. But if we read the story through the lived experiences of people who defaulted, or were evicted, then this can lead to a politics of resistance that focuses on people rather than banks.

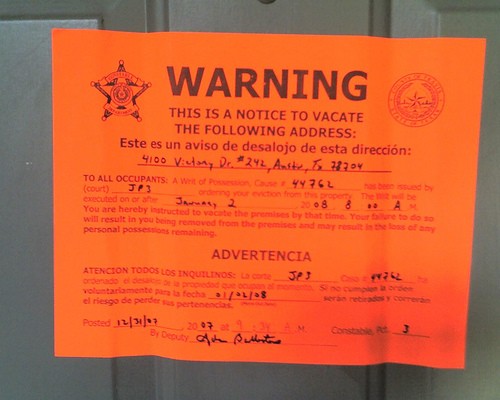

The lived experience of default and eviction

Spain had a huge housing bubble with a large share of households (around 80%) being homeowners. It also had a large percentage of people in unstable and low-paid work, meaning that a lot of homeowners had sub-prime mortgages. Because there is no personal bankruptcy legislation in Spain, many of the half a million households that have been evicted since the crisis have carried their mortgage debt with them alongside homelessness. This situation has left hundreds of thousands of households without a home, while being hundreds of thousands of Euros in debt.

During my research in 2014-16, I conducted a series of interviews with people who have experienced eviction or the imminent threat of eviction. The stories they tell show the realities of what it is like to experience unpayable mortgage debt:

Susanna: “The worst moment was when we went to social services and they gave us a ‘nutrition kit’. Within there were these packets of instant soups. As I had prepared it that evening and I was feeding my daughter with it I stopped and thought. An instant soup that only contains salt, which from a nutritional point of view gives my daughter nothing. So that a bank can charge [mortgage repayments] , my daughter has to be malnourished. That’s when I decided to stop paying [the mortgage] and that I wouldn’t care what the bank told me. Until I got to that point where I had to choose whether to eat or pay [the mortgage], the bank took all that it could from us”.

For many, the worst experience is the time before mortgage default, when anxiety and fear of eviction increase.

For Susanna and many others, one of the worst experiences is the period before defaulting on the mortgage. This is when you cannot make ends meet and anxiety and fear over the consequences increase. Once people have stopped paying their mortgage, the situation does not get better. Banks and debt collectors use a combination of tactics that border on harassment and bullying:

Ana: “I was going crazy, I couldn’t sleep. The phone wouldn’t stop ringing from the bank and I stopped answering it. Day and night, they called. The doctor had to give me pills. Many times, I thought that I’m going to get a pistol and I’ll go and shoot that bank manager and then myself. I thought a lot about committing suicide.”

Soraya: “There were sometimes forty phone calls daily, from eight in the morning until ten at night…but the calls to me weren’t the worst. It was the ones to my mother as the guarantor. I was thinking, she’s ill and on top of that she finds herself in this situation and it’s my fault because all she did was trying to help me…and unlike me she didn’t hang up, she tried to explain the situation to them and it really distressed her when they didn’t listen.”

Roberto: “I developed a phobia against phones during the darkest times that I have still not got over. I still don’t have a phone. But the worst was when our daughters answered. They would try to explain but ended up crying. The people from the bank said ‘your parents are thieves, they are criminals’.”

There were also cases where the banks threatened parents to get social services to take their children into care. Naturally, these experiences often lead to anxiety, depression and anger.

Half a million households have been evicted from their houses in Spain as a result of the financial crisis

From dispossession to resistance

But the stories of the four interviewees quoted above are not ones of powerlessness and hopelessness. They are all part of the Spanish social movement Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca (PAH) or Platform for the Mortgage-Affected. Through the PAH, Susanna first obtained debt eradication and social housing at affordable rent. Then, after becoming a leading figure in PAH Barcelona and helping hundreds of households to do the same, she began working for the city council with housing issues.

Ana also achieved debt eradication after years of struggle and negotiating with the bank with the support of the PAH. She lives in the same flat that the bank wanted to evict her from, but now as a social tenant. Roberto lives in a flat in a building belonging to a bank that the PAH has occupied with the aim of forcing the council to appropriate it and have it as social housing. The PAH have been struggling for the right to housing and against the profiteering of the financial sector that has taken place to the detriment of Spanish households, by using a combination of civil disobedience and campaigns to change the law.

Seven days at PAH Barcelona - Introduction to the Platform for the Mortgage-Affected and Social Movement 'PAH'

The PAH builds its resistance against the banks and the state on the personal experiences of its members. Together, they stop each other from getting evicted by gathering to block the way of bailiffs and police. This is generally successful and saving each other’s homes builds a strong camaraderie in the movement. Listening to a family thank a hundred people who have turned up and managed to stop an eviction is a heartfelt experience that shows the capacity of collective agency.

The PAH also occupies bank branches to force banks to negotiate debt eradication and social housing provision for one or more households. Some of these occupations have lasted weeks and they can be an outlet for the emotions that many people feel:

Maria: “That first bank occupation was [like a huge relief]. Getting rid of all those fears, feeling all that adrenaline. I ended up really tired but like floating. All that anger that we had inside, there that day we let it go. And I said: My God!, nobody can stop me now. All the fear that I had and now nobody can stop me.”

The PAH occupies a branch of the Spanish banking group BBVA

One thing that is remarkable with the PAH’s campaigning is that people actually win their individual struggles with the bank and obtain debt eradication and social housing by stopping evictions, occupying banks and squatting. The PAH calls these achievements ‘small great victories’. This means that there is a constant stream of people, victims of the housing crisis, who become political activists that fight for each other and for a radical overhaul of Spanish housing and mortgage legislation and politics. To be sure, they are up against mighty enemies in the form of multinational banks and Wall Street vulture funds, but the struggle continues. Building resistance on everyday experiences of crisis and dispossession is something that others can learn from and something that shows the importance of looking for the everyday when we study the economy. Not just because we should care about people’s experiences out of compassion, but because people are agents for change when acting collectively without fear.

Evictions Resources

Berglund, O., 2017. Contesting Actually Existing Austerity. New Political Economy, 0(0), pp.1–15. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2017.1401056.

Colau, A. & Alemany, A., 2012. Mortgaged Lives, Barcelona: Cuadilatrelo de Libros. Available at: https://www.joaap.org/press/pah/mortgagedlives.pdf

Di Feliciantonio, C., 2017. Social Movements and Alternative Housing Models: Practicing the “Politics of Possibilities” in Spain. Housing, Theory and Society, 34(1), pp.38–56. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14036096.2016.1220421.

Di Feliciantonio, C., 2016. Subjectification in Times of Indebtedness and Neoliberal/Austerity Urbanism. Antipode, 48(5), pp.1206–1227. Available at: http://doi.wiley.com/10.1111/anti.12243.

García-Lamarca, M., 2017. From Occupying Plazas to Recuperating Housing: Insurgent Practices in Spain. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 41(1), pp.37–53.

PAH, Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca – website of the platform for the mortgage affected

De la burbuja a la Obra Social/From the bubble to community housing – video with english subtitles

These Photos Show the Reality of Spain’s Housing Crisis – photo series by the Time Magazine