The word graffiti is derived from the Italian, graffio, meaning to scratch or inscribe. Graffiti is one of several related terms – see also street art, muralism, pixacao, stenciling – used to describe words or images that have been etched, scrawled or painted onto walls, pavements or other surfaces, usually outdoors and/or within public view. Examples of graffiti date back to ancient times, with individuals making their mark in the homes, temples, marketplaces and iconic edifices of early civilizations from Athens and Pompeii to the Yucatán Peninsula. However, in recent years, the spread and popularity of graffiti across the globe has ignited new research agendas that cut across disciplinary divides. While historians have surveyed graffiti as a supplementary source of commentary on processes of social and political change, criminologists have often taken a greater interest in the more ‘illicit’ dimensions of the practice by exploring the motivations of taggers and the ‘effectiveness’ of punitive measures for curbing their activities. We might therefore wonder whether graffiti is a socially legitimate form of expression and testimony, or, a kind of social deviance requiring intervention and resolution?

A range of ethnographic works examine the expressive, embodied and performative elements of graffiti production. Taking a predominantly urban focus, these studies acknowledge how graffiti and street art has come to form “a community of practice with its own learned codes, rules, hierarchies of prestige, and means of communication“. By observing, interviewing and engaging with such communities of practice, scholars can provide valuable insights into the lifeworlds and environments that graffiti writers and street artists themselves inhabit, the ways that they perceive of their own actions vis-à-vis broader society, as well as the ways that the experience and practice of inscription; the invention and remixing of styles, motifs and icons can itself shape and alter one’s sense of self and of possibility.

Graffiti as resistance

Graffiti has often emerged as a mode of political expression and an instrument of protest. Its non-institutionalized and low-tech nature make it an accessible channel and resource through which marginalized actors can communicate their views. Holly Eva Ryan demonstrates some of the ways that graffiti and street art have been used to counter and resist authoritarian regimes in Latin America. Drawing on the work of James C. Scott, she demonstrates how urban inscriptions can operate as forms of ‘everyday resistance’. In particular, when faced with a repressive government machinery, members of the public and the political opposition may well be seen to play along with the regime’s demands and principles out of concern for their own safety and that of those around them. Yet, offstage they will always find creative ways to question and challenge the status quo.

'The murals speak of my rights' - Graffiti and Street art are often used as a form of political protest.

Anonymised slogans (“Down with the dictatorship”; “Democracy lives”; “Freedom to political prisoners”), elaborate graphics produced under the cover of darkness, and seemingly abstract interventions that come about as a result of aesthetic free play can all work together to break the complicity of silence under authoritarianism and erode its power. By providing an expressive space where others have been shut down, graffiti circumvents attempts at censorship and it reminds the public that there is an alternative discourse, ideology or way of doing things. By tapping into an existing cultural stock of metaphors, icons and symbols graphic interventions can stimulate an emotional response, igniting anger, restoring hope or fuelling disgust at the status quo.

By the same token, there is sometimes a restorative or cathartic element to graffiti production. As a creative act, it enables artists or writers to reach beyond the realities and limits of day to day life, to give form to their feelings and, in the words of one Argentine street art collective, “get out all the shit that makes [them] sick“.

Graffiti and street art have also been deployed as a means of neutralizing the influence of corporate advertisers. The practice of ad-jamming or culture jamming refers to deliberate efforts by artists and writers around the world to obstruct or subvert the perceived ideological programming that takes place via billboards, posters and other forms of commercial media aimed at selling particular products and lifestyles to contemporary consumers. As the collective Notes from Nowhere describe:

“Culture jamming ranges from the simple alteration of billboards – with spray paint or pasted up text using similar fonts, the redesign of logos, the printing of spoof newspapers such as The Financial Crimes to more complex forms involving hacking websites, or developing intricate press pranks. Although the techniques and media vary, there is one key characteristic: the subversion should look and feel like the real thing.”

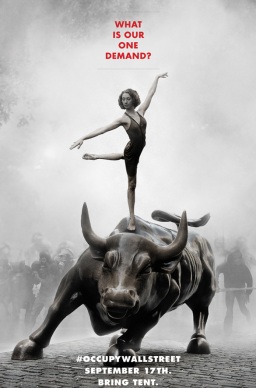

Among the world’s best-known culture-jammers are the Adbusters Media Foundation, a nonprofit outfit founded in 1989 that has specifically committed itself to disrupting and challenging the proliferation and dominance of commercial advertising in public and digital space. Adbusters today constitutes a global network of artists and graphic designers, numbering over 100,000. The group is better known for the design and dissemination of political posters, such as the now popularised image of a ballerina dancing on the back of a sculpted bull, which became one of the mobilizing symbols of the Occupy Wall Street movement. Nonetheless, members of the network also include graffiti writers and street artists whose subversive urban interventions can be photographed, uploaded and shared among an increasingly decentralized, transnational and digital community of activists and spectators.

Graffiti and recuperation?

Julia Tulke and Andrzej Zieleniec among others, interpret the practice of culture jamming within the wider context of battles over ‘The Right to the City’. Drawing on the work of Marxian theorist Henri Lefebvre, these scholars explore the role of graffiti and related urban interventions in contesting the socio-spatial norms that have emerged as a consequence of the increasing commodification and control of public and social space in modern times. In this view, graffiti and its related urban forms can be understood as attempts to participate in the re-making and reinvention of cities according to the needs and desires of residents; and, as a disruption of attempts by states and big business to privatize and apportion urban space in ceaseless pursuit of profit. Implicit in these kinds of arguments is the idea or belief that street art and graffiti offer an effective form of critique and resistance to capitalism in its more pernicious neoliberal forms; that it can, in the words of the Frankfurt School philosopher Herbert Marcuse,

“break open a dimension inaccessible to other experience, a dimension in which human beings, nature and other things no longer stand under the law of the established reality principle….The encounter with the truth of art happens in the estranging language and images which make perceptible, visible and audible that which is no longer, or not yet, perceived, said or heard in everyday life.”

However, the extent to which street art can effectively free itself from state and market imperatives is itself up for question. The work of other Frankfurt School scholars, particularly that of Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer, reminds us to be cognizant of the ways that artistic forms can also become appropriated and have their critical powers blunted under capitalism. The pair famously used the term “culture industry” to describe the commodification of cultural forms that had resulted from the expansion of capitalism into new areas. The culture industry, they argued, does not emerge from the spontaneous efforts and desires of the masses; rather it is engineered from above by the ruling classes. It plays a central role in cementing its audience to the capitalist status quo by absorbing their discontents with cathartic storylines, emotive musical riffs and providing distraction from surrounding inequities and forms of exploitation.

Graffiti and street art are no exception to the rule. As Martin Irvine writes, what initially began “as an underground, anarchic, in-your-face appropriation of public visual surfaces… has now become a major part of visual space in many cities and a recognized art movement crossing over into the museum and gallery system”. Moreover, as technological advances have made it simpler to document, map and share images across the world, the emerging popularity of graffiti has not gone unnoticed by governments and corporations who have themselves taken steps to appropriate the medium for their own ends.

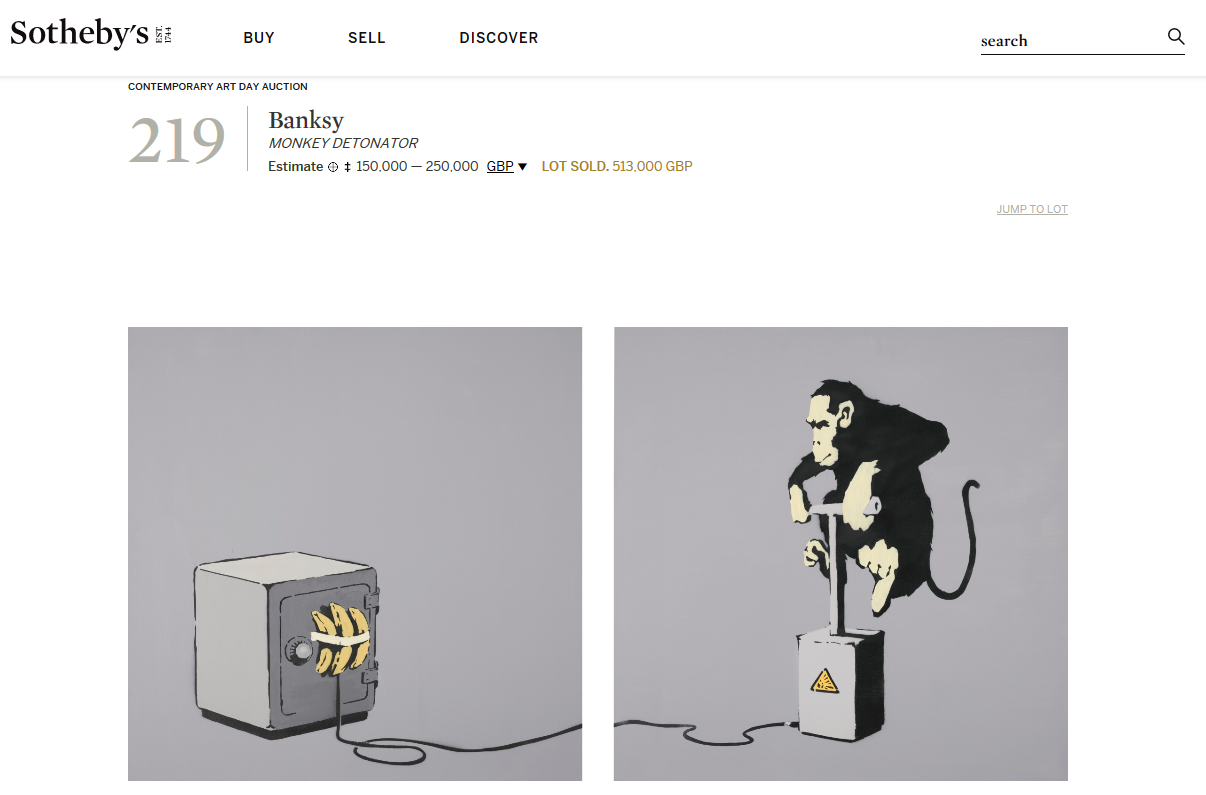

Hence, in recent years we have seen street art and graffiti incorporated into an ever-widening portfolio of urban regeneration programmes, community cohesion projects, and corporate rebranding initiatives whose ultimate interest is in profits rather than people. Examples abound. Since the mid 2000s, national and local governments in some Latin American states have moved to decriminalise graffiti; others have loosened restrictions in order to create ‘free painting zones’ in urban centres. Works by internationally-recognised street artists including France’s Jean-Michel Basquiat and Mr Brainwash, and of course Britain’s Banksy now sell for hundreds of thousands, sometimes millions, of pounds at auction.

Screenshot from Sotheby's website. On 8 March 2018 they auctioned Banksy's 'Monkey Detonator' for £513,000.

These kinds of developments demonstrate the growing recognition that certain forms of graffiti can be successfully commodified, either sold on to private bidders as exclusive art objects or providing a visually stimulating environment that can be exploited to boost revenues from the tourist and rental markets (see also Travel Guides). In the United Kingdom for example, Bristol’s popular street art festivals frequently attract thousands of visitors. In 2012, the See No Evil festival saw up to 50,000 street art aficionados descend on the city, each one spending hard earned cash on accommodation, food, drink and more. As Athlyn Cathcart-Keays points out in The Guardian, even without having a dedicated event, “for every painted wall in a city there is most likely a tour to go with it. A three-hour graffiti walk around the streets of Shoreditch could set you back £20, and in colourful Buenos Aires a tour of the decorated walls can cost $25 (£16)”. Just what this does for the disruptive and liberating potentials of graffiti and street art however, is not entirely clear.

Bristol's See No Evil block party. Credited to TMV_Media @Flickr

Graffiti Resources

Brewer, D.D. and Miller, M.L. (1990) ‘Bombing and burning: The social organization and values of hip hop graffiti writers and implications for policy.’ Deviant behavior, 11(4), pp.345-369.

Feigenbaum, A. (2010) ‘Concrete needs no metaphor: Globalized fences as sites of political struggle.’ Ephemera: Theory & Politics in Organization, 10(2), pp.119-133.

Zieleniec, A. (2016) ‘The right to write the city: Lefebvre and graffiti.‘ Environnement Urbain/Urban Environment, (10), online edition.

Baird, J., Taylor, C. and John, W. (2010) (Ed.) Ancient graffiti in context. London: Routledge.

Irvine, M. (2012) The work on the street: Street art and visual culture in Heywood, I. and Sandwell, B. (Eds) The handbook of visual culture. London: Bloomsbury, pp.235-278.

Ryan, H.E. (2016) Political Street Art: Communication, Culture and Resistance in Latin America. London: Routledge.

Aesthetics of Crisis – A blog and ongoing research project on political street art and graffiti in Athens in the context of the crisis, curated by Julia Tulke.

Adbusters.org – Website of the adbusters collective, including an archive of spoof ads.