Written by Prof Sophie Harman

Pili and the ‘left ones’

‘Ah, so she’s a left one?’ asked Nkwabi. Nkwabi is a popular actor in Tanzania and we were discussing him potentially appearing as the only professional actor in the film I was making, Pili. The rest of the cast is made up of real people from the rural part of the coastal region of Tanzania and the story of the film is based on their lives.

‘A left one?’ I asked.

‘A left one, left by their partner, has children, but is alone.’

The character of Pili is a left one. She is a single mother with two children, working an informal job in the fields and managing competing demands on her time and her HIV Positive status as she tries to make a better life for herself and her children. The film can thus be seen as a microcosm of how poor people exercise agency and try to navigate the structures that produce affliction. From the structures you can see – such as dilapidated transport infrastructure, busy medical clinics, and intensive manual labour – to those you can’t, like gendered family roles and discrimination. While global responses to health ‘emergencies’ like HIV tend to focus on getting the right kind of expertise and medicine to affected areas, this everyday perspective reveals the kind of mundane politics that really matter: is there running water? Can I drink it? And who can help me get it?

Trailer of 'Pili'

The burden of disease

As a left one, Pili – like thousands of other women in rural Tanzania – is burdened with care responsibilities for her children and has to rely on a network of friends, balancing acts, and the resilience of the children themselves to manage their upbringing. Her care burden is framed by quotidian notions of risk – can she take her children with her? Should she leave them at home and hope for the best? – and regular confrontations with the temporality of need. This refers to her inability to plan for her future and that of her children against the pressing urgency of food, school books, and maintaining her home. These care responsibilities are compounded by her work as an agricultural labourer. Again this requires an exertion of agency – day-to-day negotiations are needed to ensure she is paid correctly – as well as being physically arduous and precarious. A bad farming season on account of poor weather and Pili and her family will struggle to eat.

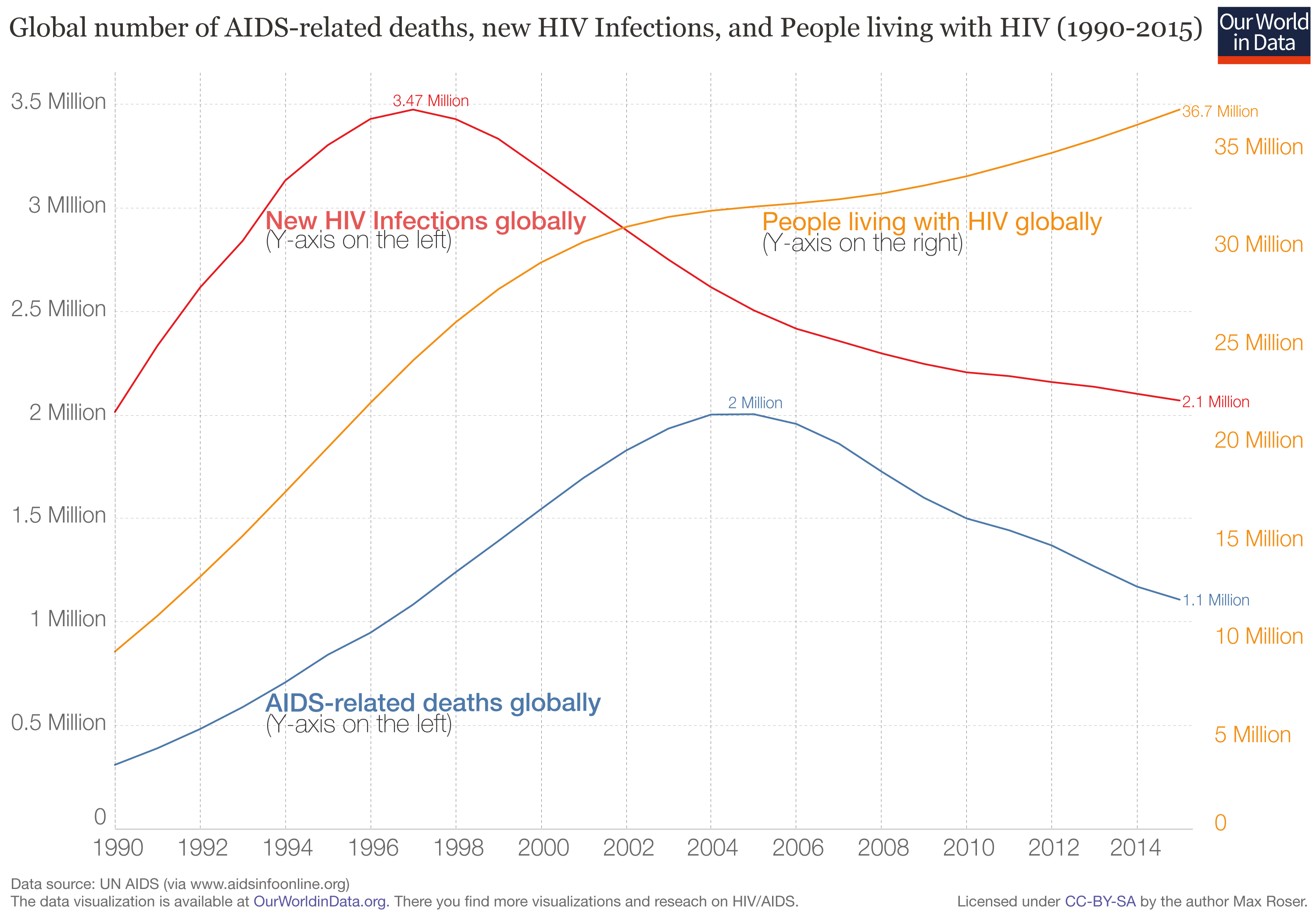

The result of this ongoing strain on body and mind is a steady erosion of Pili’s own health, which in feminist political economy scholarship could be conceptualised as depletion: the sacrifice by women of their own well-being as they involuntarily support wider processes of capital accumulation and patriarchal authority through productive and reproductive work. Whereas diseases like HIV/AIDS are often discussed in terms of the numbers of individuals dying from the illness, this reminds us that living with and being widowed by HIV/AIDS also profoundly affects people’s lives.

HIV/AIDS in numbers. Source: ourworldindata.org

The (ab)uses of the informal economy

The term ‘informal economy’ typically refers to economic activities not recognised or regulated by the state. For Pili these are encountered in a variety of ways; some which enable her cause and others which hinder it. The main focus of the film is how Pili can get the money she needs to rent a coveted market stall. To do this she has to go through the men who own the land and decide who can or cannot become a stallholder. Meanwhile, to get a loan to secure a deposit she has to convince the ‘Vikoba’ micro-lending group to give the money. In both cases those who can help her use the situation to maximise their own power base and self-interest, highlighting that these formal procedures are in fact imbued with misogyny and gatekeeping, as well as being influenced by inter-personal favours and local rumour.

But informality also provides opportunity. Anti-retroviral treatment that helps people living with HIV manage their status and live healthy lives is free in Tanzania. It is financed by the government and funding initiatives such as George W. Bush’s President’s Emergency Plan for HIV/AIDS Relief (PEPFAR) and the Global Fund to Fight HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. These formal provisions are thus available to Pili. However, Pili prefers the informal provision of anti-retroviral treatment, paying the local dispensary for under the counter drugs with the little money she has, which allows her to keep her status a secret and hide from the close community in which she lives. Pili is in a sense self-stigmatizing; ashamed of her HIV Positive status and keeping it to herself. This is a common story. Across Africa free treatment and care is often available, yet a mere one-third of those eligible are able to access it. Healthcare provision cannot be understood solely with reference to the affordability of medicine.

The Treatment Action Campaign in South Africa has sought to de-stigmatise HIV/AIDS. Picture: flickr.com

Explaining the prevalence of HIV/AIDS

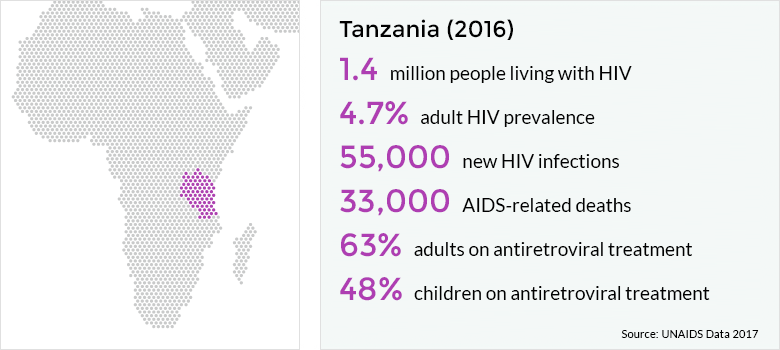

The wider narrative of the film is about the human impact of HIV/AIDS. Sub-Saharan Africa has the highest population of people living with HIV/AIDS in the world. Tanzania has an adult prevalence rate – the percentage of people aged 15-49 living with HIV/AIDS in the population of the country – of 4.7%. This is relatively low in comparison to a state such as South Africa, which has a prevalence rate of 18.9%, but relatively high in comparison to state such as France with a prevalence rate of 0.4%.

HIV and AIDS in Tanzania. Source: avert.org

Explanations as to why sub-Saharan Africa has such high prevalence rates tend to be explained by the behavioural approach or the poverty approach. The behavioural approach suggests that it has to do with norms in African societies that encourage unsafe sex and mother to child transmission: concurrent and polygamous partnerships and marriages; the family where large numbers of children is commonplace; and high levels of religious faith wherein condom use is discouraged.

The poverty approach suggests that the epidemic is driven by low levels of education, which result in limited awareness of the risks of the disease and how to avoid infection. Poverty also prevents people accessing health services and affording medicine, as well as requiring them to undertake risky economic activities such as prostitution. Both of these explanation have flaws, for example the behaviouralist approach has been criticised for being imbued with racial metaphors of the hyper sexualised African male, and the poverty approach has been criticised for being too deterministic.

Cross-cutting both the behavioural and poverty approach to HIV/AIDS are gender relations as a determining driver of disease. There are more women living with HIV/AIDS than men. Lack of access to property rights and professional employment roles limits the ability of women to negotiate safe sex with partners. Lack of access to reproductive health services prevents women managing their own sexual health and reproductive planning. Yet by the same token, men do not access care and treatment services for HIV/AIDS as much as women and so more likely to die of AIDS-related illnesses than women.

A large number of women contract HIV from their partners who then leave them when they disclose their HIV status. The left ones often find out about their HIV status when screened as part of antenatal services. They are thus left to manage the news that they are HIV positive, undertake treatment to prevent their child being born with HIV, and potentially come to terms with being a left one, left by the partner that created the situation they find themselves in. And as we have seen, women also then take on the care responsibilities for family and wider community members, as well as voluntary roles as peer educators and counsellors. HIV/AIDS is not a health issue, in the sense that it can be bracketed out from politics and studied purely as a medical phenomenon. It is a disease driven to large extent by gendered inequalities; social relations that can and must be changed.

The psychological trauma of living with HIV in South Africa

In Pili we can see how the wider structures of society shape the intimate experiences of health at the individual level. Yet there is no Pili. She was played by Bello Rashid, and as Bello was keen to point out, she was not acting out her own life but that of a character. Pili also does not represent every women living with HIV/AIDS in Tanzania or even in the small town of Miono. However when finalising the story for the film and discussing it with the cast to ensure it was an authentic as possible, one of the cast members, Sesilia, simply stated, ‘Pili is everywhere.’ The rest of the group nodded with quiet assent.

Bello Rashid as Pili. Picture: Facebook

HIV/AIDS Ressources

Anderson, E.-L. (2015) Gender, HIV, and risk: navigating structural violence. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

Harman, S. (2010) The World Bank and HIV/AIDS: Setting a global agenda. London: Routledge.

Lisk, F. (2009) Global Institutions and the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Abingdon: Routledge.

Poku, N., Whiteside, A. (Eds.). (2004). The Political Economy of AIDS in Africa. London: Routledge.

Elbe, S. (2008). Risking lives: AIDS, security and three concepts of risk. Security Dialogue, 39(2-3): 177-198.

Harman, S. (2011). The dual feminisation of HIV/AIDS. Globalizations, 8(2): 213-228.

Johnston, D., Kevin D., and Rizzo M. (Eds.). (2015) Special Issue: The Political Economy of HIV. Review of African Political Economy, 42(145): 335-496.

O’Laughlin, B. 2015. Trapped in the prison of the proximate: structural HIV/AIDS prevention in southern Africa. Review of African Political Economy 42(145): 342-361.

MTV Shuga – Kenyan television drama series addressing issues of responsible sexual behaviour.

We were here – Movie about five longtime San Franciscans whose lives were transformed by the the AIDS epidemic in the early 1980s.

Fire in the Blood – Movie about the aggressive blocking of access to low-cost AIDS drugs by Western pharmaceutical companies.

Sarah Boseley. (2016). Think the AIDS epidemic is over? Far from it – it could be getting worse. The Guardian.

Abigail M. Hatcher. (2015). HIV can be prevented in babies if their Mothers are kept safe. The Conversation.

The Economist. (2017). Some good news and some bad, in the fight against HIV. The Economist.