Written by Dr David Bailey

Shaping welfare states

In debates surrounding the restructuring of the welfare state in advanced industrial democracies, a key question relates to national policy autonomy. To what degree can democracies decide on a particular configuration of welfare policies in the context of global economic constraints? For example, the possibility for a country to have comprehensive employment benefits might be compromised by calls for the cost of labour to be competitive so as to attract international investors. Or perhaps the provision of universal healthcare might be undermined by the need to keep taxes low and budgets balanced so as to maintain confidence within financial markets that states will repay their debts.

Contributions to international political economy that have used a comparative methodology to compare the effects of globalization on different countries have argued that convergence of welfare states around a pared-back liberal model associated with the US and UK can be avoided, and that other policy arrangements and social contracts between state and society are possible. In these studies the continued capacity for political parties, the electorate and organized labour to determine public spending, social expenditure and/or welfare generosity are highlighted. Similarly other scholars have shown how the same global pressures have different effects depending on the variety of capitalism they encounter, distinguishing between coordinated market economies and liberal market economies and arguing that the former are relatively more resilient.

Whereas the role of popular mobilization and protest in inhibiting welfare retrenchment is commonly noted, empirical research has tended to focus on the impact of more institutional forms of political activity, such as party competition and trade union density, in determining welfare reform outcomes. Such an institutional or ‘elite-oriented’ focus overlooks innovative and ‘elite-challenging’ types of political activity.

This is especially important since it is during times of low economic growth and heightened global pressure that institutional ‘vetoes’ – the ability to stop something happening – become less effective. This is because people within these institutions accede to the claims that adjustment to the rigours of the market is necessary and because they can be more easily ignored by decision-makers. It is precisely at this point, when ‘normal’ hierarchical politics does not adequately represent societal interests, that disruptive and horizontally-organized political action comes to the fore as a bulwark against welfare retrenchment. Simply put: resistance is not futile.

Austerity in the UK

The global economic crisis marked by the collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008 prompted governments across Europe and North America to move to shore up their financial industries. As a result, by 2010 many of these governments subsequently found themselves with heightened levels of public debt. In seeking to address this issue, almost all of these countries subsequently turned towards an austerity agenda in an attempt to bring down public spending. In the UK this so-called ‘age of austerity’ is most obviously associated with the emergency budget delivered by the Conservative and Liberal Democrat coalition government almost immediately after entering office. Yet the ‘age of austerity’ also witnessed a counter-movement, what we might consider as a corresponding ‘age of dissent’.

This dissent has seen members of the general public increasingly turn to extra-parliamentary and unconventional forms of protest politics in an attempt to push issues onto the political agenda; issues that the established political actors – parties, ministers, parliamentarians – seem increasingly unable or unwilling to take up. Some of these issues related to funding cuts for public services and social security benefits, others to attempts to make people work in the formal sector for less money (e.g. via workfare unemployment schemes or real wage reductions in public sector jobs). All of these reforms had been justified, in part, by the need to reduce state spending.

One question that arises about this seemingly new era of ‘permanent protest’, is how to measure and document it. In an attempt to assess the degree to which levels and types of protest have changed in the British context since the onset of the age of anti-austerity, I have created a dataset of political protest events in Britain that dates back to the mid-1980s. This can be found at the Left Parties and Protest Movements blog and records every political demonstration, protest and strike event that was reported in The Times and/or The Guardian newspapers between 2005 and 2016, as well as a representative sample of such events dating back to the mid-1980s. In total, this includes nearly 1,900 protest events. This dataset can be used to identify the key changes in the frequency and types of protest that we have seen, and to consider how these have changed over this period of time.

Profiling protest

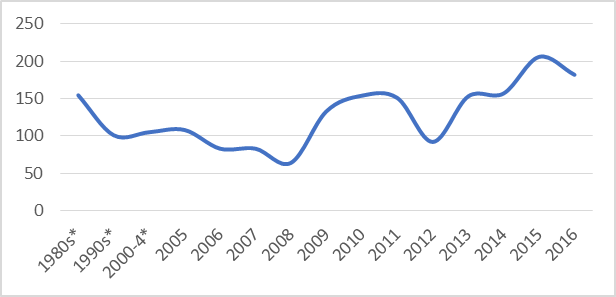

What is immediately striking is the consistently higher levels of protest activity witnessed in Britain since the onset of global economic crisis in 2008. Thus, between 2009 and 2016 the national press reported an average of 154 protest events per year, compared with only 95 per year between 2000 and 2008, and 101 per year for the 1990s.

Frequency of protest events in Britain per year, 1980s-2016

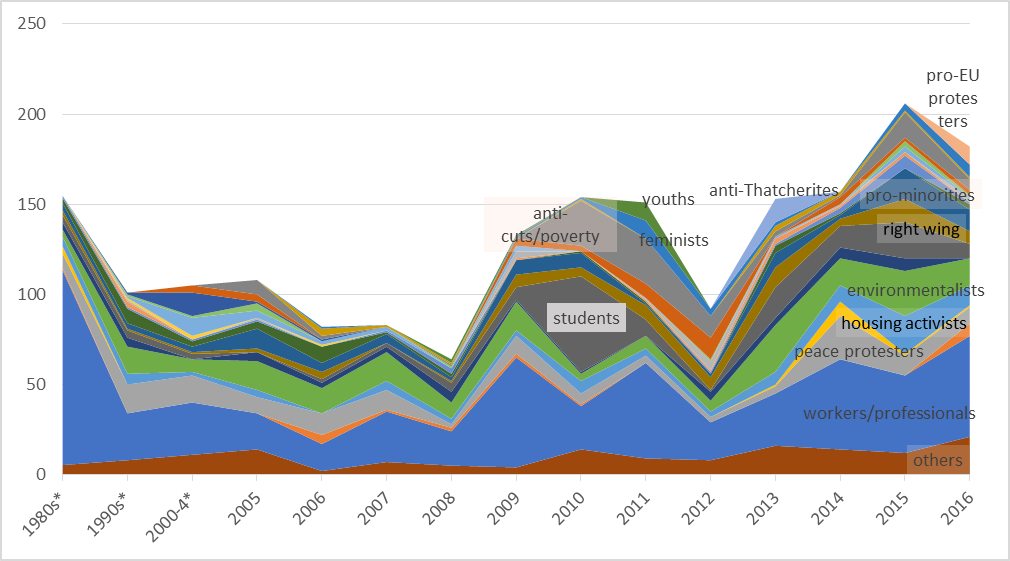

We can also break down the total numbers of protest events into key protest actor types. As the figure below shows, the post-2008 context saw a number of key actors increase in prominence in Britain’s extra-parliamentary politics. Students and ‘anti-cuts’ protesters grew considerably in importance during the initial wave of anti-austerity protest in 2010-11. The student protests were initially sparked by the occupation of Millbank Tower, then home to the Conservative Party campaign headquarters, in protest in 2010 at the announcement that university tuition fees would triple.

Frequency of protest events in Britain per year, 1980s-2016, by key actor types

Likewise, the return to inflated house prices, especially in London, saw a significant growth in housing activists between 2014 and 2016. The growing housing crisis in Britain, and especially in London, has created heightened problems of homelessness, unaffordable housing, and ‘revenge evictions’. In response, 2015 saw the emergence of an increasingly radical housing movement, led by groups such as Focus E15, Sweets Way Resists, and the Radical Housing Network – oftentimes using the occupation of unused buildings as their method of protest. Drawing attention to the exclusionary dynamics of funding cuts, one slogan used in these protests was ‘social housing not social cleansing’.

We can also use this archive of protest events in Britain to explore changes in the types of protesters engaging in these events. Perhaps predictably, one of the most important changes that we can see in terms of those engaging in protest events during the age of anti-austerity is the emergence of a new group of anti-cuts campaigners. This group accounts for 83 reported protest events between 2010 and 2016. Anti-cuts campaigners were responsible for a range of events, including the annual demonstrations that have occurred outside the Conservative annual conference since 2010, the disruptive events staged since October 2010 by UK Uncut protesters outside retail stores such as Top Shop, Vodafone and Boots, each of whom were accused of tax avoidance, the Save Our Libraries campaign that began in 2011, the 2011 March for the Alternative organised by the TUC which attracted around half a million demonstrators, the regular events organised by the People’s Assembly Against Austerity, and the campaign of 2016 which opposed the planned closure of the modern art gallery at the Royal Botanic Gardens Edinburgh.

Five other groups of activists have also become increasingly prominent during the age of anti-austerity: students, feminists, housing activists, the far right, and, most recently, those calling for Britain to remain within the European Union. Feminist protests were almost entirely unreported from the 1980s through to 2011, upon which a series of ‘slutwalk’ events took place in opposition to what were viewed as widespread and reactionary views about women within the establishment. This also marked the beginning of a period during which women’s protest events have begun to feature more in the press. More recently, Sisters Uncut have staged a number of disruptive protests that have sought to highlight the impact on women of government spending cuts to domestic violence services.

Five other groups of activists have also become increasingly prominent during the age of anti-austerity: students, feminists, housing activists, the far right, and, most recently, those calling for Britain to remain within the European Union. Feminist protests were almost entirely unreported from the 1980s through to 2011, upon which a series of ‘slutwalk’ events took place in opposition to what were viewed as widespread and reactionary views about women within the establishment. This also marked the beginning of a period during which women’s protest events have begun to feature more in the press. More recently, Sisters Uncut have staged a number of disruptive protests that have sought to highlight the impact on women of government spending cuts to domestic violence services.

Finally, as is often the case in times of austerity, nationalism has also re-emerged as an issue in British politics. This increase in far right activity can also perhaps in part explain the growing anti-EU sentiment witnessed, eventually resulting in the Brexit vote in June 2016. This, in turn, has also prompted a new pro-Remain movement, witnessing ten reported events held by pro-Remain supporters in 2016.

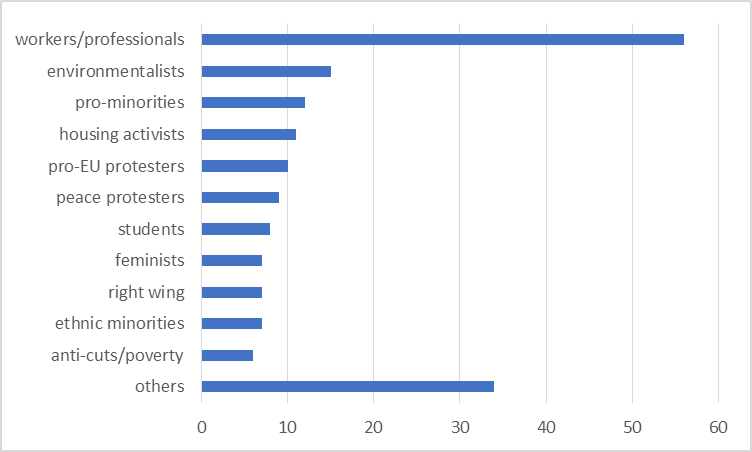

Frequency of protest events in Britain, 2016: key actors

As we can see, if we take a snapshot of protest events held in Britain in 2016, we see that workers and professionals remain (and have remained throughout the period) the key group of protesting actors. This especially included the junior doctors and the rail workers’ dispute with the train operator Southern Rail. It also included smaller more independent actions taken by workers – for instance, walkouts and protests against both Deliveroo and Uber, so-called ‘platform services’ which do not act an employer but engage workers as ‘independent contractors’ – and a dispute in demand of the living wage for workers at a number of Picturehouse and Cineworld cinemas across London.

The place of protest

Whilst the use of newspaper data obviously comes with its limitations when we seek to chart the different trends in protest that we see around us – not least because the mainstream media oftentimes remains uninterested in what for many of us are the most interesting elements of political activity – nevertheless, having a record of the events that are reported hopefully allows us to see into some of the broader headline political trends occurring outside of the formal sphere of parliaments, governments and political parties. By making this data available, moreover, it is hoped that others will be able to use it to explore and access those trends, perhaps making it increasingly possible for us to uncover what ‘works’ when it comes to our attempts to make those who are in power listen to, and heed, our demands, especially when we seek to oppose (and hopefully block) their damaging austerity agenda.

Indeed, in research conducted with Saori Shibata (Leiden University) we compared different forms of opposition to austerity measures in both the UK and Japan and found that resistance against austerity measures tends to be most successful when it is part of a combination of (a) everyday forms of dissent, (b) disruptive public protest, (c) non-disruptive public protest, and (d) militant forms of refusal. This implies different settings and forms of opposition – moving, for example, from marches in the street to get the ear of government, to complaints in the workplace about the impact of funding cuts, or blockades in the household to prevent council evictions.

This research raises further questions still. Is there a danger that protest and disruptive politics pushes up welfare generosity in the short-term but impairs economic growth in the long-term, thus creating increased pressure for welfare reform in the future? Does anti-austerity politics have any historical parallels with the ‘Third World austerity’ experienced by developing countries under structural adjustment policies in the 1980s? And how do modes of protest spread across countries, recasting what is considered ‘political’ and how this is pursued?

Protest Resources

Bailey, D. (2009) The Political Economy of European Social Democracy: A Critical Realist Approach London: Routledge

Gamble, A. (2016) Can the welfare state survive? Malden, UK: Polity

Pierson, P. (1994) Dismantling the welfare state? Reagan, Thatcher and the politics of retrenchment Massachusetts, US: Harvard University Press

Bailey, D. (2015) Resistance is futile? The impact of disruptive protest in the ‘silver age of permanent austerity’, Socio-Economic Review, 13(1): 5-32

Hay, C. (2006) What’s globalization got to do with it? Economic interdependence and the future of European welfare states, Government and Opposition, 41(1): 1-22

Worth, O. (2016) The battle for hegemony: Resistance and neoliberal restructuring in post-crisis Europe, Comparative European Politics, online, 1-17

Left parties and protest movements – resources on different kinds of political movements

Protest politics: Introduction – a 2016 introduction from the co-editor of Dissent magazine