Written by DR BEN RICHARDSON

Food inequality

There is a paradox at the heart of the global food system: in Raj Patel’s pithy phrase, the world population is 'stuffed and starved’. In 2021 the World Health Organization reported that 1.9 billion adults were deemed overweight or obese, while 462 million were underweight. Although these manifestations of malnutrition might be embodied in different ways, they can be seen as symptomatic of similar underlying causes of poverty and discrimination. Arguably it is these social inequalities that account for the mal-distribution of food; inequalities which are perpetuated by the very way in which the food system functions. This is no accident, of course. For all the harm it has caused, the paradox of food has been good for profits.

A study of sugar has much to tell us about this situation. On the one hand, the way sugar production is organised has denied millions of people the means to buy or grow enough food to feed themselves. The reasons for their poverty differ. Workers have been exploited through low wages or made redundant by mechanisation, farmers have been indebted or marginalised in favour of large landowners, and rural dwellers have lost livelihood opportunities or been squeezed from their land. Yet the end result has been the same. Vulnerable people have not received a fair share of the wealth produced by the sugar industry, and in some cases, have actually been harmed by its more rapacious practices.

On the other hand, many of the so-called junk foods that constitute poor quality diets contain added sugar and other sweeteners. By changing the taste of products and engaging in extensive marketing campaigns, food manufacturers and retailers have been able to transform dietary habits and re-organise patterns of consumption. Average worldwide sugar intake more than quadrupled during the twentieth century with levels of obesity and diabetes following close behind. And since these patterns of consumption are socially stratified, they both manifest and mark out these hierarchies. One example can be found in oral health, since tooth decay is closely linked to sugary foods. Due to differences in diet and dental treatment borne out over a lifetime, the poorest people in England end up with five fewer teeth than the richest.

Such inequalities are not solely down to someone’s socio-economic position. Hierarchies based on gender, race, nationality and other differences are equally important and frequently intersect at the individual level. For instance, because of the different ways their work is valued, a female labourer from the Dalit caste weeding sugarcane in India earns much less than a white male farmer sowing sugar beet in Germany. The question we explore here, then, is: how are inequalities reproduced through food?

Nova Olimpia, Mato Grosso, Brazil. Trucks loaded with sugarcane plants enter the mill.

Capitalist commodities

The starting point is to consider sugar first and foremost as a capitalist commodity. According to Karl Marx, a commodity is something produced by human labour which has a use-value for others. Although it did not necessarily have to be sold via a market but could be bartered or collectively redistributed instead, Marx also recognised that the realisation of the exchange-value of commodities through the market was being generalised to such an extent that social inequality had become readily accepted as the natural result of the different prices fetched by products that people happened to labour on. He dubbed this the ‘fetishism' of commodities and believed that it concealed the exploitative class relations of capitalism.

Since the 1990s, the production of sugar as a capitalist commodity has globalised. This has been entrenched by developments including the formation of the World Trade Organisation, which has liberalised trade and undermined national farm policy, and the industrialisation of China and marketization of food provisioning across the Global South, which has underpinned a seismic nutrition transition. As a result, the contradictions associated with contemporary capitalism, as played out through sugar, have extended and intensified. For example, the systematic over-production of sugar has led to periodic market crashes and exacerbated a global diabetes epidemic. These in turn have produced crises (a farm crisis, a health crisis) which state authorities have been called upon to manage. Contrary to the common assertion that equates capitalism with free markets, it is often capitalists themselves have called for state intervention, either to make a market function in their interests or else to protect them from the vagaries of it.

At the same time as taking global capitalism seriously, it is also important not to ascribe it with uniform and omnipresent characteristics. As argued by Andrew Gamble, ‘capitalism need not be a single fate’. This refers both to the different ways in which capitalist economies can be organised and the limits to which capitalist principles of private property, commodification and endless accumulation extend. Think of the bake-a-cake sales that raise money for charity. These are just as much part of the economy as a factory making chocolate bars or a futures exchange trading sugar contracts. This creates some room for human agency, without which every eventuality would be boiled down to the inner workings of capital – no better than other deterministic accounts of sugar which attribute outcomes to its irresistible sweetness or the characteristics of the cane plant.

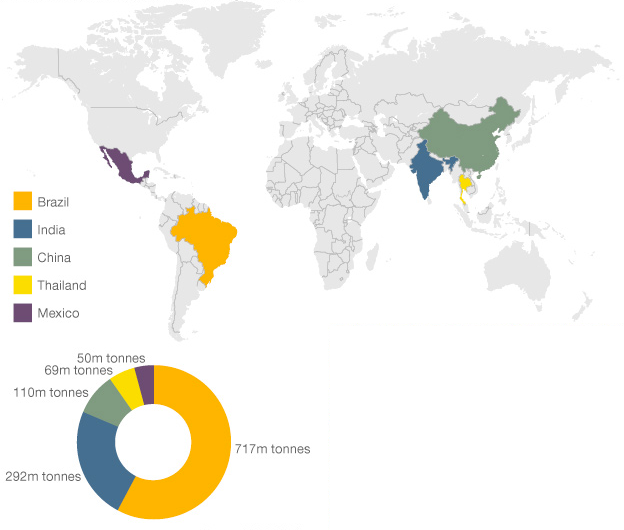

The largest producers sugar cane. Source: UN, 2010

Circulating capital through sugar

Many political accounts of food focus either on the supply of food (e.g., who gets agricultural subsidies) or on the demand for food (e.g., who gets to eat well). Taking a specific commodity like sugar and tracing its supply-chain allows us to make the connections between the spheres of production, exchange and consumption. Treating it as a capitalist commodity, meanwhile, allows us to contextualise this in terms of the dynamics of capital accumulation and its attendant social relations.

In the sphere of consumption, the sale of sweet-tasting and long-lasting sugary foods and drinks have helped food manufacturers and retailers to break down established dietary structures and sell more products. This gave them a powerful incentive to promote the continued consumption of sugar through coordinated cultural manipulation, even in the face of mounting evidence from the medical establishment around its ill-effects. In the sphere of exchange, moves by state authorities toward the liberalisation of trade and investment flows have made it easier for global capital to profit from their exchange, whilst simultaneously limiting the policy space previously used to protect domestic producers. Finally, in the sphere of production labour and land have been treated in similar ways under capitalist agriculture; exploited and exhausted in the unending quest to earn more money. But the precise way in which this has been carried out has differed, shaped by the boom and bust dynamics and prevailing political consensus in particular places – the latter forged largely by opposition from organised labour and social activists to the industry’s most abusive practices.

Across each of these spheres, different alliances and antagonisms can be identified. For instance, while sugar millers and farmers have presented a united front to influence state agricultural policy, they have also clashed in industry negotiations over the price of the sugar crop. What this shows is that the commonplace reference to ‘the sugar lobby’ can be easily misused since, depending on the point in question, there might be as much that divides businesses as unites them. What we should refer to instead are what André Drainville calls cliques and fractions of capital. Cliques of capital are temporarily brought together by support for a particular policy, whilst fractions of capital have common interests that are incorporated in a long-term strategy organised through trade associations, pressure groups and links with political parties and state departments. During the twentieth century, it has been the industrial fraction of capital, constituted by sugar mills and food manufacturers and brought together around their desire for the mass production of sweetened industrial foods, which has been most influential in shaping sugar policy.

At the same time, the organisation of the sugar industry is not static. Inter-capitalist conflict will continue to drive change of its own accord as different businesses build their profitability as fast as they can. For example, the role of financial capital in sugar has become much more significant in the twentieth century. Moreover, this does not happen in a bubble. Health professionals, state planners, organised labour and social activists have all pushed and pulled on the accumulation process, shaping the bounds of permissible practice. While the circulation of sugar is structured by capitalism, capitalism need not be a single fate.

Valuing life differently

How then should the pathologies of the global food system be treated? For some people, the answers to are to be found in technical modifications, such as reformulating products with low-calorie artificial sweeteners or boosting crop yields through by planting high-yielding seeds. We should be wary of such technical solutions and their underlying commodity fetishism. Whilst reducing sugar consumption may lower some people’s risk of diabetes, if those same people remain reliant on poor quality food then they remain vulnerable to other forms of diet-related ill-health. Similarly, increasing crop productivity may help farmers make a decent living, but only insofar as they are not then subject to price cuts by other businesses in the supply-chain.

We should be wary of such technical solutions and their underlying commodity fetishism

A progressive politics of sugar should not be about changing people’s relationship to the commodity itself, but about changing our relationships to one another. This change comes about through site-specific struggles to value life differently. They are site-specific because they take different forms in different places: a campaign against child advertising here, a protest against water pollution there. But what they have in common is a desire to govern by a different metric, one that recognises values beyond ‘the bottom line’, be it the sanctity of childhood or the preservation of the environment. At their furthest reaches, these contestations might cohere into broader change that would make sugar provisioning more ecologically sound and socially just. This is a transition that must ultimately challenge the profit-driven organisation of food and farming itself.

Eaters of the world, unite. You have nothing to lose but your fast-food chains!

Sugar Resources

Fakhri, M. (2014) Sugar and the Making of International Trade Law (Cambridge, UK: University of Cambridge Press)

Mintz, S. (1986) Sweetness and Power: The Place of Sugar in Modern History (London, UK and New York, US: Penguin)

Richardson, B. (2015) Sugar (Cambridge, UK and Malden, US: Polity Press)

Guthman, J. and DuPuis, M. (2006) ‘Embodying Neoliberalism: Economy, Culture, and the Politics of Fat’, Environment and Planning D, 24: 3, pp. 427-448.

McGrath, S. (2013) ‘Fuelling Global Production Networks with ‘Slave Labour’? Migrant Sugar Cane Workers in the Brazilian Ethanol GPN’, Geoforum, 44, pp. 32-43.

Richardson, B. and Richardson-Ngwenya, P. (2013) ‘Documentary Film and Ethical Foodscapes: Three Takes on Caribbean Sugar’, Cultural Geographies, 20: 3, pp. 339-356.

Bonsucro sugarcane certification organisation

Behind the Brands campaign by Oxfam

Food Politics blog by Marion Nestle

Sugar Coated documentary about sugar politics and health

The Price of Sugar documentary about sugar production in Dominican Republic

Understanding the Sugar Market educational video about commodity trading