Written by Dr Juan Ignacio Staricco and Prof Stefano Ponte

Glocalisation

Our journey into the global economy begins with a bottle of Malbec over dinner. Every wine has a story behind it, and like other consumers, we look for this on the bottle’s label. It reads:

For over four generations, the Catena Zapata family has grown vines on the foothills of the Andes. Catena Malbec is sourced from the family’s historic high-altitude vineyards in Mendoza, Argentina. From the marriage of these historical parcels emerges a wine of unique character that has natural balance, concentration and a distinct varietal identity.

This text exhibits a variety of elements that are typical of the world of wine. There is a strong emphasis on tradition. Mastering the art of winemaking is presumed to take years, even generations, of experience with vineyard tending and wine production. There is also a link between the quality of a wine and a specific terroir, the unique combination of soil, climate and know-how that is found in a specific place. The popular imaginaries that connect tradition, terroir and quality together emphasize the importance of localness; a provenance that is captured on labels and increasingly protected by geographical indications too.

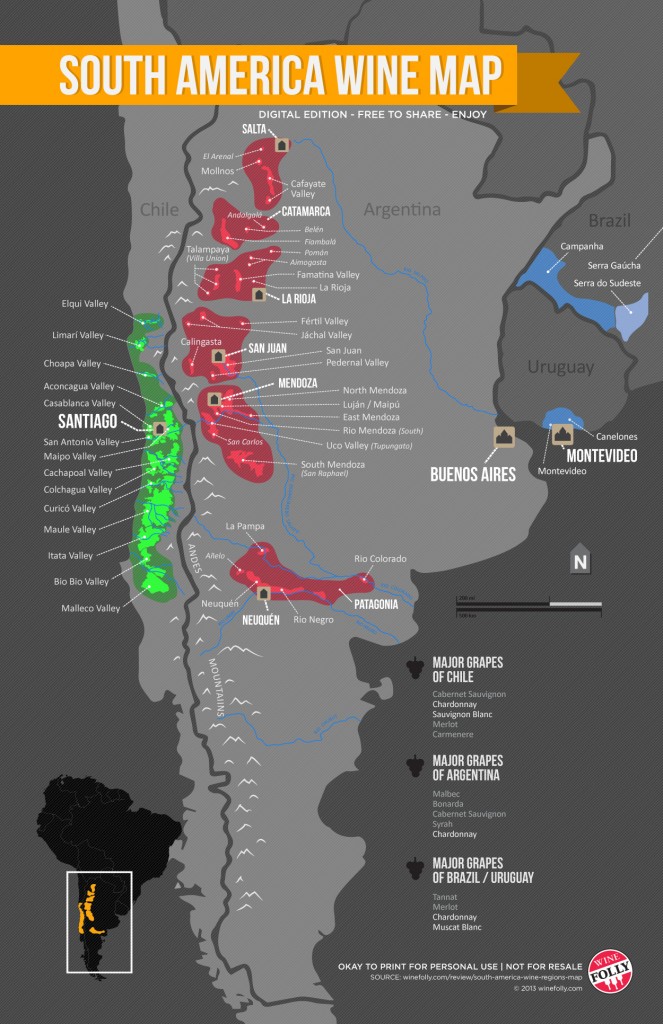

Yet as shown by our casual purchase of the Malbec – 12,000km from where it was made – in other respects wine has become truly globalised. Historically the drink has been dominated in both symbolic and economic terms by European producers. But in the second half of the 20th century, things started to change. The 1976 Paris Wine Tasting provides the landmark moment when European domination started to wane – two US wines defeated their French counterparts in a blind tasting! Producers in the US had compensated for their lack of traditional know-how and a well-known terroir with the development of technologically innovative and scientific method of production, pioneering a style that came to be known as new world, a reference to the colonial territories of the Americas, Africa and Australasia where they were made.

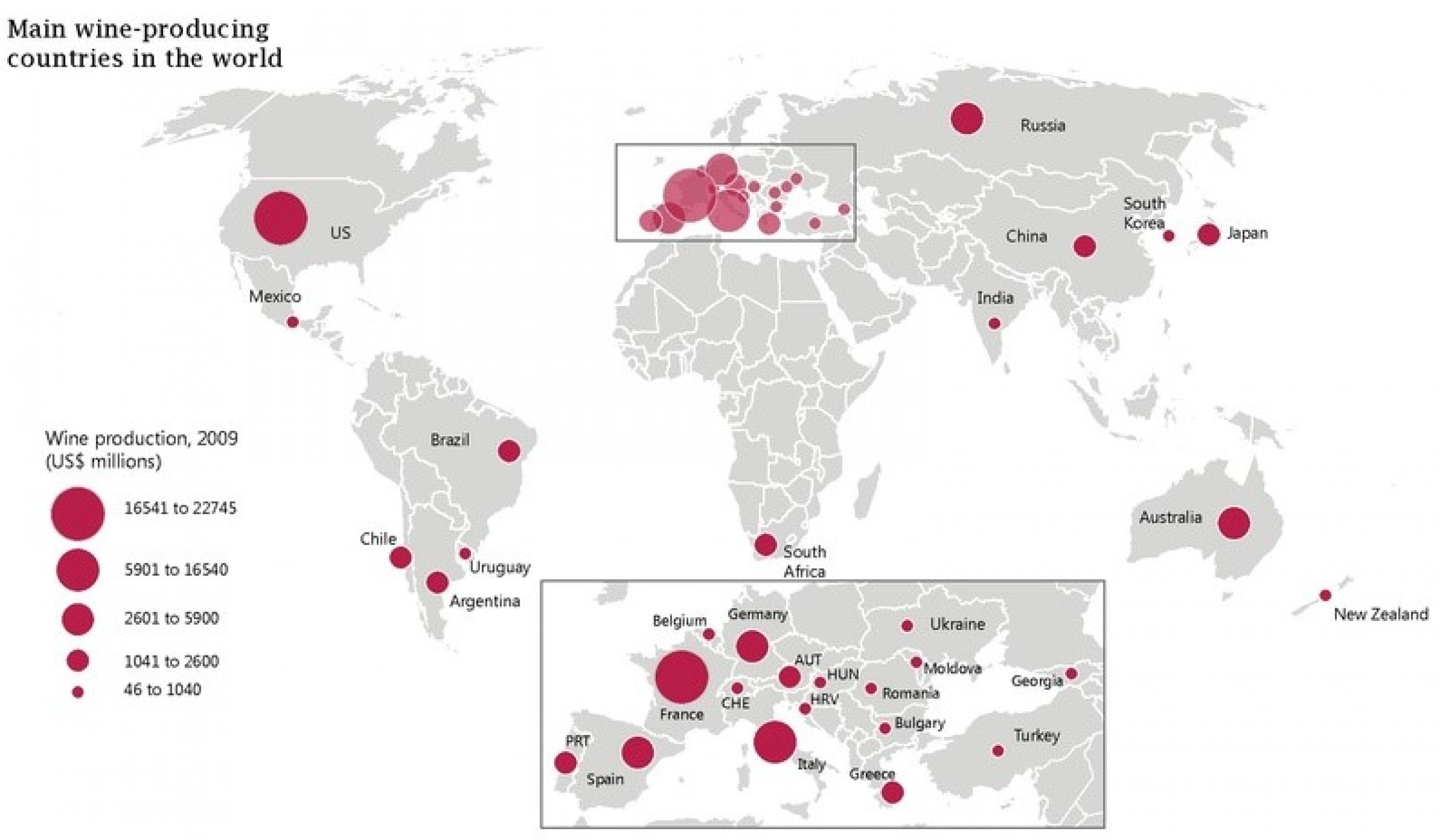

From the 1970s onwards important changes in global wine consumption began to take place. Countries with historically high consumption like France, Italy and Spain started to drink less. At the same time, demand started to grow at a fast pace in non-traditional markets such as the US, the UK, Russia and China. A shift in preferences also began to occur in favour of the fruity and fresher wine styles offered by new world producers. From the early 1990s to the early 2000s, the new world producers increased their share of global production from 18% to 27% and their share of global exports by value from 6% to 23%. The scale of economic competition had been truly extended.

Global wine production in 2009

From quantity to quality

We started our story with a bottle of Malbec because this grape is a great example of the uneven dynamics of globalisation. The first Malbec vines arrived to Argentina in the middle of the 19th century from France, where it had a poor reputation (Malbec derives from mal bouche, meaning bad taste). Malbec was widely planted in Argentina although for more than a century it was only used to make a table wine of poor quality, sold at low prices within the national market and consumed as a staple household good. However, during the 1970s and 1980s this ‘productivist’ or growth-oriented regime suffered from a scissor movement of over-supply and declining demand. The crisis which befell Argentinean producers prompted them to pursue the US path. But to export wine that satisfied the tastes of affluent consumers, they would have to undergo a radical process of conversion, moving from a focus on quantity to on one quality.

This required a shift from generic wines to varietal wines based on a single grape, and a major investment in viticulture and international marketing. Financial support for this came from foreign investors encouraged by the liberalisation of capital markets under the Menem government of the 1990s. A second policy fillip came in 2002 when the peso was devalued leading the price of Argentinean exports in other currencies to suddenly drop. Changes were also necessary in the wage relation. Vineyards producing for these wineries became less reliant on family labour and contratistas – relatively autonomous seasonal workers given housing on site – and more reliant on a nucleus of permanent staff educated in modern viticulture combined with reserve of temporary workers to be contracted in for time-bound tasks.

Yet not all wineries went in this direction, resulting in a dual structure of production in the country. On the one hand, we find a steadily growing quality-led industry that produces high-value wines mainly for export. On the other hand, we find a declining quantity-led industry that produces low-value wine for domestic sale. The lower profitability of the latter industry has led to the disappearance of many smaller winemakers. In the country as a whole, there are now just 1,250 wineries left, with six of these accounting for 70% of all production.

Malbec meets Fairtrade

Fairtrade certification is probably the best-known initiative attempting to improve the livelihoods of small agricultural producers and rural workers in the global South by giving them better terms of trade. To do so, Fairtrade International has developed standards for producers, plantations and traders which seek to shape their operations in the direction of social, economic and environmental sustainability, e.g. by requiring buyers of wine grapes to have annual sourcing plans in place. In exchange, certified businesses get access to market niches in important wine consuming countries (such as the US, the UK, and Sweden) and the economic benefits that go with this, including credit facilities, price premiums, and a minimum price settled independently of market conditions.

Fairtrade certification is probably the best-known initiative attempting to improve the livelihoods of small agricultural producers and rural workers in the global South by giving them better terms of trade. To do so, Fairtrade International has developed standards for producers, plantations and traders which seek to shape their operations in the direction of social, economic and environmental sustainability, e.g. by requiring buyers of wine grapes to have annual sourcing plans in place. In exchange, certified businesses get access to market niches in important wine consuming countries (such as the US, the UK, and Sweden) and the economic benefits that go with this, including credit facilities, price premiums, and a minimum price settled independently of market conditions.

While the label is usually associated to products such as bananas, coffee, tea and cocoa, Fairtrade wine emerged more than a decade ago. Since Fairtrade only certifies production in certain poor countries, this wine is currently sourced from just four places: South Africa, Chile, Argentina and Lebanon. In Argentina, the adoption of Fairtrade could have strengthened the financial position of the smaller wineries and improved the lives of some of the 132,000 growers and workers still employed in the sector. But because Argentinean wine exports consist of higher quality wines, Fairtrade has ended up certifying producers, including some of the dominant ones, based in the more profitable part of the industry. So, despite being the ones facing declining prices, producers of generic red table wine have been locked out this potential value-adding strategy. This contributes to the reproduction of an unequal system in Argentina, and gives us reason to critique the kind of simplistic stories of North-South solidarity that Fairtrade and its supporters often portray.

UK supermarket chain The Cooperative on Fairtrade wine from Argentina

Ethical trade

How might Fairtrade wine be put on a more sure ethical footing? Because of the emphasis Fairtrade puts on empathy between (affluent, white) consumers in the global North and (poor, non-white) producers in the global South, the ‘alterative’ approach of French philosopher Emmanuel Lévinas is a suitable starting point. Lévinas proposes that social justice involves moving between two moments. One is an encounter of radical alterity; of seeing someone so different you feel an immediate responsibility to them. The second is choosing between the various responsibilities you have thereby assumed and facing down the challenge of comparing the incomparable.

Fairtrade only approximates this notion of justice. The encounter of radical alterity is not fully realized as the consumer sees the face of ‘the Other’ on the product label or video advertisement, but only as a fixed image. They do not get to see us back. And the choice of responsibilities is fudged. Fairtrade compromises in the toughness of its standards and levels of its pricing for the sake of commercial viability. Following Lévinas with conviction would require Fairtrade to assist the Other unconditionally, in this case by supporting the struggles of marginalised producers and workers whatever they might be. This would require a more uncompromising and overtly political stance to be taken, but also would be more likely to lead to genuine transformation in social relations. Despite the facile message sometimes conveyed by the idea of socially-responsibly shopping, Lévinas reminds us that being ethical shouldn’t be easy.

Wine Resources

Anderson, K. (ed) (2004). The World’s Wine Markets: Globalization at Work. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

Colman, T. (2008). Wine Politics: How Governments, Environmentalists, Mobsters, and Critics Influence the Wines We Drink. Berkeley, US: University of California Press.

Itcaina, X., Roger, A. and Smith. (2016). Varietals of Capitalism: A Political Economy of the Changing Wine Industry. Ithaca, US: Cornell University Press.

Ponte, S. (2009). ‘Governing through Quality: Conventions and Supply Relations in the Value Chain for South African Wine’, Sociologia Ruralis, 49(3), pp. 236-257.

Staricco, J. I. and Ponte, S. (2015). ‘Transforming Quality Regimes: A Regulation Theory Reading of Fair Trade Wine in Argentina’, Journal of Rural Studies, 38, pp. 65–76.

Staricco, J. I. (2016). ‘Fair Trade and the Fetishization of Levinasian Ethics’, Journal of Business Ethics, 138(1), pp. 1-16.

The Wine Economist – blog on the global political economy of wine

United States Department of Agriculture Wine, Beer and Spirits – data and analysis

Wines of Argentina – industry association marketing

David Roach and Warwick Ross (2013) Red Obsession – on the struggle by the great chateaux of Bordeaux to meet demand for their rare and expensive wines from China

Sky Pinnick (2011) Boom Varietal – on the Malbec wine boom in Argentina

Jonathan Nossiter (2004) Mondovino – on the impact of globalisation on the world’s different wine regions