Written by Dr Chris Browning

On the evening of 13 November 2015 Paris was rocked by a brazen set of terrorist attacks that left 130 people dead and a further 368 injured. The targets of the attacks were ordinary people doing ordinary things, walking home after work, eating at restaurants, attending a music concert, and settled in with friends on café terraces. The attacks generated a sense of crisis in the city that quickly spread across France and beyond. If it could happen in Paris then it could happen anywhere. Indeed, metropolitan narratives of Parisian joie de vivre seemed to be in doubt. A mimetic response swept across social media. People – Parisians, French nationals and Europeans, more broadly – began to proclaim ‘Je suis Paris’ and covered their Facebook and Twitter accounts with the French flag. With more resonance in Parisian culture, a hashtag quickly caught hold: ‘Je suis en terrasse’ – literally, I am on a sidewalk. The Je suis en terrasse meme was a celebration of Parisian café culture, and was characterised by people posting pictures of themselves drinking coffee and wine in cafes and elsewhere, an apparent act of defiance and courage against as yet unknown perpetrators.

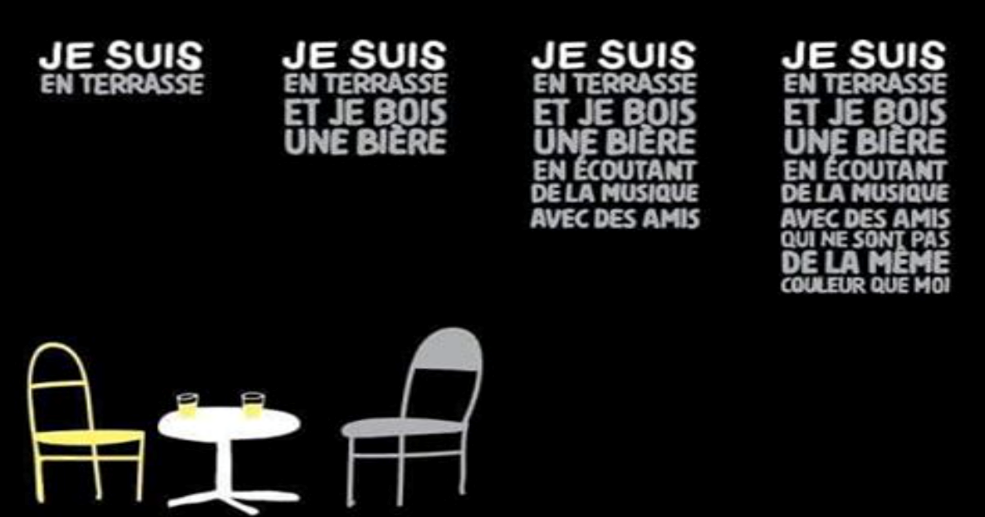

Source: Le Bonbon magazine. Translation: I am on the sidewalk and I drink a beer listening to music with friends who are not the same colour as me.

In this way, Parisian café culture became a focal point for political expression as people sought to establish a sense of what was happening, why, and what to do next. One element of this was that the decision to reoccupy cafes and publically proclaim ‘Je suis en terrasse’, possibly wearing a t-shirt with a ‘Je suis Paris’ slogan was actually very brave. In a context in which some of the attackers remained unaccounted for, and when the safety of public spaces was highly uncertain, going en terrasse was to consciously court danger and vulnerability; actively gaining a sense of purpose, meaning and vitality, rather than the traditional state narratives of securing and making safe. There was a sense that Parisian joie de vivre was at stake and reclaiming the terrasse was configured as a virtuous action; a reaffirmation of identity. As one Parisian student reflected: “This weekend I have close friends coming to Paris and [we] are going to celebrate life for them [the victims]”.

We are all on the terrace

Interestingly, the affirmation of French café culture did not stop at #jesuisenterrasse, but grew to reflect a general sense of France’s place in the global order. A moral economy of civilizational community emerged that prioritised certain cultural values over ‘others’. As one reader of a story featured in The New York Times asserted:

France embodies everything religious zealots everywhere hate: enjoyment of life here on earth in a myriad of little ways: a fragrant cup of coffee and buttery croissant in the morning, beautiful women in short dresses smiling freely on the street, the smell of warm bread, a bottle of wine shared with friends, a dab of perfume, children playing in the Luxembourg Gardens, the right not to believe in any god, not to worry about calories, to flirt and smoke and enjoy sex outside of marriage, to take vacations, to read any book you want, to go to school for free, to laugh, to argue, to make fun of prelates and politicians alike, to leave worrying about the afterlife to the dead.

In this framing, it is precisely the everyday, routine behaviours of the French that are seen to draw a line between the civilized and uncivilized. This was also evident in responses on Western media that sought to capture the public mood, and where again Parisian café and culinary culture was a notable feature. For example, two days after the attacks John Oliver, a US-based British comedian and presenter of the popular HBO satire news programme Last Week Tonight proclaimed that the attackers would fail and France would endure because: “If you’re in a war of culture and lifestyle with France, good fucking luck! Go ahead, go ahead, bring your bankrupt ideology, they’ll bring Jean Paul Sartre, Edith Piaf, fine wine, Gauloises cigarettes, Camus, camembert, madelaines, macaroons, Marcel Proust and the fucking croquembouche”.

In more serious tones, Andrew Neil, a respected political broadcaster on the BBC, responded by labelling the attackers a “bunch of loser jihadists” trying “to prove the future belongs to them, rather than a civilization like France”. He too then went on to provide an even longer list of French cultural, historical, economic, scientific and culinary achievements, which he contrasted to the contributions of ISIS:

Beheadings, crucifixions, amputations, slavery, mass murder, medieval squalor, a death cult barbarity that would shame the Middle Ages… Whatever atrocities you are currently capable of committing, you will lose. In a thousand years’ time Paris, that glorious city of lights, will still be shining bright, as will every other city like it, while you will be as dust along with the ragbag of fascists, Nazis and Stalinists that have previously dared to challenge democracy, and failed.

While such heartfelt responses are clearly executed at a time of acute emotional need, we must also question the politics of such sentiments.

The politics of everyday life

Everyday life is often mundane, a procession of humdrum activities and routinized practices: getting up with the alarm, having a wash, eating breakfast, commuting to work, working, shopping, paying bills. But we should not confuse the ordinary, everyday and mundane with the inconsequential. For instance, psychologists tell us that our daily routines are actually fundamental to our ability to ward off potentially crushing existential anxieties about the meaning of life and our own limited lifespan. On this view, routines can provide a sense of stability and order that enables us to ‘bracket out’ existential concerns and ‘go on’ with everyday life.

Daily routines can produce and confirm our own biographical narratives; the self-identity that we cultivate, which can underpin a more secure sense of subjectivity and agency in the world. Everyday routines can help us to perform for ourselves and others a sense of our identity (e.g. as a man, husband, father, lecturer etc…). But there is also a collective element to this. Everyday routines often link self-understandings to wider collective identities (e.g. of family, friends, sports teams, religion, nationhood, etc.). Indeed, individuals often generate a sense of self-esteem, status and reflected glory by living vicariously through the broader achievements of the groups with whom they identify, e.g. Manchester United fans. As performances of self-identity, and of self-identity in relation to others, our routines are therefore important in establishing a set of expectations about the world and one’s place, purpose and role within it.

Our daily routines are also of interest to sociologists, who tell us that aside from providing an essential psychological defence mechanism against existential anxieties of nonbeing, they are also fundamental to what Norbert Elias famously termed “the civilizing process”. Everything from everyday habits of how we hold a knife, use cutlery (or not), all the way through to drinking coffee, and more particularly how we drink coffee – at the café, en terrasse – operate as markers of what different cultures view as civilized behaviour. Adherence to particular cultural practices of the everyday can therefore act as markers that confirm a sense of status, belonging and shared emotional or cultural knowledge. At the same time, of course, they may also help to draw (hierarchical) boundaries between insiders and outsiders.

The everyday is global

In Elias’ terms the Je suis en terrasse meme crystallized the café, and Parisian café culture, as a civilizational marker of considerable significance, where being en terrasse became a fundamental expression of the community’s core values. One effect of this was to ascribe meaning, value and purpose where meaning, value and purpose at first seemed to be missing – to the deaths of so many ordinary people doing ordinary things.

In the examples provided by John Oliver and Andrew Neil, we see how the response to the attacks was culturally framed, not only in France, but also beyond. The presentation of Paris as a spiritual centre, and the listing of French cultural achievements – reminding ‘us’ of ‘our’ cultural achievements in comparison to the nihilism of ISIS – essentially reconfigured the attacks as an attack on the West at large. Thus the café was symbolically transcribed into a civilizational script where the West must struggle against a securitized enemy, an ‘other’ depicted as nothing short of barbarian savages.

Another 'civilizational script' of modern France. Credit: Yann Caradec via Flickr.

Framed this way, the everyday practice of going to a café becomes central to a civilizational politics of community building and differentiation. It is a locus of meaning, a site of civilizational (and civilized) struggle imbued with enhanced purpose and significance. Other examples exist of course. Recall how, after 9-11, President Bush called on Americans to “go shopping”, “conduct business” and “go to Disneyworld”. However, while such collective affirmations (and hierarchies) are often framed as acts of resilience – a refusal to surrender fear to the terrorists – these affirmations of everyday consumption can also be depoliticising, suppressing any need to raise uncomfortable questions about whether or not we might also bear some responsibility for the nature of the situation?

Indeed, we might question whether such collective affirmations of a particular form of culture, or civilisation, might – despite the explosive ripples they send round social media – foster a more passive, less critical form of citizenship? Yet with the attackers depicted as uncultured, uncivilized savages, such questions were not broached. The heartfelt eulogies to Paris, its people and café culture, provided a background against which President Hollande could frame a call for “merciless” war against Daesh, in the name of civilisation.

Cafe Resources

Elias, N. (2000). The Civilizing Process. Oxford: Blackwell.

Giddens, A. (1991). Modernity and Self-Identity. Cambridge: Polity.

Tillich, P. (2014). The Courage to Be. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Browning, C. S. (online first) ‘“Je suis en terrasse”: Political Violence, Civilizational Politics, and the Everyday Courage to Be’, Political Psychology.

Crang, P. (1996) ‘Displacement, Consumption, and Identity’, Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 28: 1, 47-67.

Jafari, A. and Goulding, C. (2008) ‘”We are not terrorists!”: UK-based Iranians, Consumption Practices and the ‘Torn Self”, Consumption, Markets & Culture, 11: 3, 73-91.